Back Out of the U.S.S.R.: Carter and the Boycott of the 1980 Moscow Games [Going Public Case Study #3]

The Box Score

Jimmy Carter announced his intention to boycott the 1980 Moscow Olympic Games over the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan.

Carter soon found he had no legal authority to issue such a boycott.

Carter then “went public” to convince the United States Olympic Committee (U.S.O.C.) to boycott the Games, which it eventually did.

This case is one of the few successes presidents enjoyed “going public” on sports.

The 1980 boycott also illustrates the “two presidencies” thesis, which contends presidents have more success in foreign policy than domestic policy.

[Note: This is the final of three case studies of presidents “going public” on sports. The previous two cases—George W. Bush’s discussion of steroids in the 2004 State of the Union address and Bill Clinton’s attempt to resolve the 1994-95 MLB strike—showed the limitations of the presidential bully pulpit. Carter and the 1980 boycott is the exception.]

The Complete Game

The previous two case studies about presidents “going public” on sports—George W. Bush’s discussion of steroids in the 2004 State of the Union address and Bill Clinton’s attempt to resolve the 1994-95 MLB strike—showed the limit of the bully pulpit. The exception to the rule that going public on sports doesn’t work is Jimmy Carter’s boycott of the 1980 Moscow Summer Olympic Games. What distinguishes Carter from the others is that his appeal involved an international crisis rather than a domestic matter.

(This essay focuses narrowly on Carter’s going public strategy. For an in-depth look at this case, I encourage you to read Nicholas Evan Sarantakes’s excellent Dropping the Torch or his 2014 article in Politico.)

Background

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan on Christmas Day 1979 was another lump of coal for Jimmy Carter. The Carter administration was already dealing with an energy crisis, stagflation, the ongoing Iranian hostage crisis, and a primary challenge from Ted Kennedy. Now, they faced intense pressure to reverse the Soviet invasion with no real way to do so.

As was the case throughout the Cold War and is still true today with the war in Ukraine, the U.S. studiously avoided a shooting match with the Russians that might bring about World War III. Ruling out a military response to the Soviet invasion left diplomacy and sanctions as the only options, and they were poor ones at that.

The U.S. led the international community in condemning Soviet actions, but that didn’t seem to bother Soviet Premier Brezhnev much. Carter withdrew the U.S. from the SALT II nuclear treaty; that also didn’t matter because the Senate had yet to ratify the treaty, and the U.S. had already pledged to abide by its terms, with or without the Soviets. Economic sanctions weren’t much help either because there wasn’t much to sanction: the U.S. embargoed grain shipments to the U.S.S.R., which hurt American farmers more than the Soviets. So, as is often the case when countries have no other options, the U.S. turned to sports.

Soviet troops moving into Afghanistan.

Boycotting Olympic Games, or banning countries from participating in them, had been a part of countries’ diplomatic tool kit long before the 1980 Olympics:

Austria, Bulgaria, Germany, Hungary, and Turkey were barred from competition in the 1920 Antwerp Games because of their role in World War I

Germany and Japan were likewise banned from the 1949 London Games for their role in World War II (for some reason, Italy was forgiven and allowed to compete).

The U.S.S.R. didn’t participate in the Olympics until 1952 because they thought the Games were too bougie.

The first boycott occurred during the Melbourne Games in 1956, when Spain, Switzerland, and the Netherlands withdrew in protest of the Soviet's invasion of Hungary (why the neutral Swiss decided to stay home is anyone’s guess). Egypt, Iraq, and Lebanon also withdrew in protest of the Suez Crisis.

At the 1964 Tokyo Games, North Korea, Indonesia, and China withdrew because of Japan’s aggression in WWII.

From 1962 to 1992, South Africa was banned from the Games because of its policy of racial apartheid.

Thirty-four African nations boycotted the Montreal Games of 1976 because New Zealand’s national rugby team toured South Africa in violation of an international ban.

The U.S. and 65 other countries boycotted the 1980 Moscow Games, which is our focus here. Since then…

The Soviets and 17 other communist nations reciprocated by boycotting the 1984 Los Angeles Games.

Cuba and North Korea boycotted the 1988 Seoul Games.

Ten nations, including the U.S., engaged in a “diplomatic” boycott of the 2022 Winter Games in Beijing.

Let’s set aside whether countries should boycott the Olympic Games and examine why they do. The first is symbolic. From Nazi Germany in 1936 to China in 2008 and 2022, nations have used the Olympics to sportswash their image, covering up human rights abuses with the grandeur and spectacle of the Games. One reason to boycott is to avoid being complicit in this artifice and raise public awareness of the atrocities.

The second reason is that a boycott is a low-cost coercive measure to get the host nation to change its behavior. This never works, but, hey, if sports is all you got, you might as well give it a try.

Jimmy Carter first announced he was considering a boycott in a January 4, 1980 statement:

“Although the United States would prefer not to withdraw from the Olympic Games scheduled in Moscow this summer, the Soviet Union must realize that its continued aggressive actions will endanger both the participation of athletes and the travel to Moscow by spectators who would normally wish to attend the Olympic games.” -- Jimmy Carter, “Address by President Carter to the Nation,” January 4, 1980.

After a few weeks of internal deliberations within the administration, and with no indication the Soviets planned to withdraw, Carter announced his intention to boycott in an interview with Meet the Press on January 20, 1980:

“Neither I nor the American people would support the sending of an American team to Moscow with Soviet invasion troops in Afghanistan. I’ve sent a message today to the United States Olympic Committee spelling out my own position: that unless the Soviets withdraw their troops within a month from Afghanistan, that the Olympic games be moved from Moscow to an alternate site or multiple sites or postponed or canceled. If the Soviets do not withdraw their troops immediately from Afghanistan within a month, I would not support the sending of an American team to the Olympics. It’s very important for the world to realize how serious a threat the Soviets’ invasion of Afghanistan is.” --Jimmy Carter “Meet the Press’ Interview with Bill Monroe, Carl T. Rowan, David Broder, and Judy Woodruff,” January 20, 1980.

Carter reiterated this position three days later in his 1980 State of the Union address:

“I have notified the Olympic Committee that with Soviet invading forces in Afghanistan, neither the American people nor I will support sending an Olympic team to Moscow.” --Jimmy Carter: “The State of the Union Address Delivered Before a Joint Session of the Congress,” January 23, 1980.

In a classic example of pole vaulting without a pit, Carter committed to a boycott without possessing the legal means to do so. The president did invoke powers granted to him by the Export Administration Act of 1979 to prohibit U.S. companies from financial dealings with the Games, a decision that cost N.B.C., which owned the rights to broadcast the Olympics, an estimated $87 million. (If you are of a certain age, you might recall not seeing any of the Summer Olympics in 1980 or even highlights of them. Carter’s decision is why.)

However, the U.S.O.C., not the White House, decides whether to send athletes to the games. Although the U.S.O.C. is a federally chartered non-profit, it is independent of the U.S. government and receives no federal funds. That put the Carter administration in a bind. They could either:

Convince the International Olympic Committee to relocate the Games. I.O.C. President Lord Killanin immediately quashed this idea.

Ask Congress to pass a law revoking American athletes’ passports. Few in Congress thought that was a good idea.

Carter could try to “go public” and pressure the U.S.O.C. into boycotting the Moscow Games.

There was really only one choice for Carter: he had to convince the U.S.O.C. to boycott the Games. It wouldn’t be easy. As Sarantakes points out, the U.S.O.C. governing board was initially divided on a boycott, and most American athletes were opposed. Many in the U.S.O.C. believed the Olympics should be an apolitical event to unite diverse peoples in the spirit of goodwill and friendly competition. Others felt this was a chance to stick it to the Soviets by showing up and kicking ass. For the athletes, a boycott meant years of hard work wasted and, for many, the end of an Olympic dream.

Going Public

Recall that the strategy of going public involves a president trying to change public opinion to influence some governing body, usually Congress, but, in this case, the United States Olympic Committee. Presidents go public when they can’t directly affect policy. Going public, then, illustrates the power and weakness of the White House. People listen to what presidents say. That is power. But the fact that presidents must rely on rhetoric instead of just changing policy themselves shows just how weak their position within the American system is. And while people may listen to presidents, few change their minds. This, too, is weakness.

My view is that going public rarely works. Other scholars, like George Edwards, feel the same (although, to be fair, there is an entire scholarly school of thought that finds going public can and does work). I provided two case studies that showed how Bill Clinton and George W. Bush failed in their respective attempts to go public on sports. And I can think of very few cases in American history where a president significantly moved public opinion and got the policy they wanted. Jimmy Carter’s going public on the Moscow Games is an exception.

Why did Carter succeed when so many presidents, both before and after, failed? We’ll get to this question in a bit, but let’s first consider what Carter said to the American people.

Framing the Boycott

Carter presented the case for a boycott to the American public in 40 speeches totaling 9,390 words. He focused on two points, emphasizing the first: (1) the U.S. should not be complicit in the U.S.S.R.’s sportswashing of the Afghanistan invasion, and (2) the boycott might coerce the Soviets into withdrawing. Let’s take a closer look at these frames.

Sportswashing. Recall that sportswashing refers to a nation using sports to cover up or deflect attention away from human rights abuses or bad behavior. The term can also refer to states using athletics to showcase national prowess and demonstrate the superiority of their political, economic, or social systems. Sportswashing poses a dilemma for other nations. Do you attend the Olympic Games and participate in the spectacle orchestrated by some corrupt government? Or, do you stay home in protest, depriving the host nation of the attention they crave and casting light on the evils they wished nobody saw? Carter was clearly in the latter camp. Here are just a few illustrative comments:

“It [sending U.S. athletes to Moscow] would indicate to the Soviets—and to the entire world—that the U.S. lacks the resolve to oppose Soviet aggression. It would be perceived as a vindication of the Soviet action, and you can be sure that the Soviets would so portray it.”-- Jimmy Carter: “1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow Mailgram to the President of the United States Olympic Committee on U.S. Participation in the Games." April 5, 1980.

“There is another very important, tangible, and symbolic action that we must take without delay, and that is to make it clear to the world that we will not send our nation and our nation's flags to Moscow for the Summer Olympics while the Soviets are invading Afghanistan. This is a morally indecent act on their part, and I cannot imagine the democratic or freedom-loving nations adding an imprimatur of approval to the Soviets' invasion by sending teams to the Moscow Olympics.” -- Jimmy Carter: "Interview With the President Question-and-Answer Session With Foreign Correspondents." April 12, 1980.

“The Soviets have, obviously, a great interest in the propaganda benefits to be derived for itself by an expression of participation with them in the Olympics in Moscow. Their own official publications and handbooks say that the granting to Moscow of a right to have the summer Olympics is an endorsement, in effect, of the Soviet foreign policy and a recognition of the peaceful nature of the Soviet Government. I think for a country to go to Moscow to participate in the summer Olympic Games, to raise its flag in the Olympic stadium when the host government is engaged at that moment in an unwarranted and inhumane invasion of a free and independent country is abhorrent to the moral principles on which democracy is founded.” -- Jimmy Carter: "Interview With the President Question-and-Answer Session With Foreign Correspondents." April 12, 1980.

Okay, you get the picture. But at the risk of belaboring the point, I want to call your attention to one of the more crucial speeches Carter gave during this time.

On April 10, 1980, two days before the U.S.O.C. vote on the boycott, Carter drew an analogy between the Moscow Games and the 1936 Berlin Games. The analogy was important for a couple of reasons. First, Hitler has long been the go-to analogy for presidents when they really need to move public opinion. The visceral reaction to Hitler and the lessons of Munich offer a powerful story that tells the public what to think and which policies to support. Second, Carter’s statement represents a clear departure in U.S. policy—Americans did compete in Berlin despite misgivings about the Nazis. In a Q&A with reporters, Carter stated:

“It is extremely important that we not in any way condone Soviet aggression. We must recall the experience of 1936, the year of the Berlin Olympic Games. They were used to inflate the prestige of an ambitious dictator, Adolf Hitler, to show Germany's totalitarian strength to the world in the sports arena as it was being used to cow the world on the banks of the Rhine.

The parallel with the site and timing of the 1980 Olympics is striking. Let me call your attention to one compelling similarity between the Nazi view of the 1936 Olympics as a propaganda victory and the official Soviet view of the 1980 summer games. I'd like to read to you a passage from this year's edition of the "Handbook for Party Militants," issued in Moscow for Soviet Party activists, and I quote:

‘The ideological struggle between East and West is directly involved in the selection of the cities where the Olympic Games take place. The decision to award the honor of holding the Olympic games to the capital of the world's first socialist state is convincing testimony of the general recognition of the historic importance and correctness of the foreign policy course of our country, and of the enormous service of the Soviet Union in the struggle for peace.’" -- Jimmy Carter: "American Society of Newspaper Editors Remarks and a Question-and-Answer Session at the Society's Annual Convention." April 10, 1980.

Of course, one might just as well point to the Berlin Games and draw the opposite conclusion, as Barry Goldwater (R-AZ) did on the Senate floor:

“For those of you who are concerned about making a political statement through the Olympics, please remember that Jesse Owens did more to show Hitler’s Aryan theory for the manure that it was than any boycott ever could” (Sarantakes 2010: 104).

Jesse Owens, Gold Medal 100m 1936 Berlin Games.

Coercion. The other aspect of Carter’s rhetoric was to stress that the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan was a serious threat to national security, and a boycott was an integral part of the U.S. response. Carter truly believed the part about national interest. In his 1980 SOTU, the president articulated the Carter Doctrine, which committed the U.S. to military action to protect Gulf oil and was issued as a threat to the Soviets not to move further South than Afghanistan.

He was less convinced that a boycott would do the trick. He admitted as much when he told reporters, “I don't claim that not going to the Summer Olympics will be the single factor that would result in a withdrawal of their troops.” So why talk about it?

Carter talked about a boycott as a coercive measure because presidents can never admit they are powerless in any situation, even if they are. This is unfortunate because it creates the false impression that presidents can solve any problem, even when they can’t. Carter had to give the American public some tangible response that might punish the Soviets, so why not a boycott?

The point is that when you don’t have any good options, pile up as many bad ones as possible in the hopes that quantity masks quality. In any case, here are some of Carter’s statements on the national interest and the coercive effect of a boycott:

“I regard the Soviet invasion and the attempted suppression of Afghanistan as a serious violation of international law and an extremely serious threat to world peace. This invasion also endangers neighboring independent countries and access to a major part of the world's oil supplies. It therefore threatens our own national security, as well as the security of the region and the entire world. We must make clear to the Soviet Union that it cannot trample upon an independent nation and at the same time do business as usual with the rest of the world. We must make clear that it will pay a heavy economic and political cost for such aggressions. That is why I have taken the severe economic measures announced on January 4, and why other free nations are supporting these measures. That is why the United Nations General Assembly, by an overwhelming vote of 104 to 18, condemned the invasion and urged the prompt withdrawal of Soviet troops.” -- Jimmy Carter: "1980 Summer Olympics Letter to the President of the U.S. Olympic Committee on the Games To Be Held in Moscow." January 20, 1980

“While this invasion continues, we and the other nations of the world cannot conduct business as usual with the Soviet Union. That's why the United States has imposed stiff economic penalties on the Soviet Union. I will not issue any permits for Soviet ships to fish in the coastal waters of the United States. I've cut Soviet access to high-technology equipment and to agricultural products. I've limited other commerce with the Soviet Union, and I've asked our allies and friends to join with us in restraining their own trade with the Soviets and not to replace our own embargoed items. And I have notified the Olympic Committee that with Soviet invading forces in Afghanistan, neither the American people nor I will support sending an Olympic team to Moscow.” -- Jimmy Carter: "The State of the Union Address Delivered Before a Joint Session of the Congress." January 23, 1980.

“The continuing Soviet aggression and brutality in Afghanistan has shocked and horrified nations and people the world over. It jeopardizes the security of the Persian Gulf area and threatens world peace and stability. In these circumstances, a U.S.O.C. decision to send a team to Moscow would be against our national interest and would damage our national security.” -- Jimmy Carter: "1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow Mailgram to the President of the United States Olympic Committee on U.S. Participation in the Games." April 5, 1980.

“I made a speech to the Joint Session of the Congress, State of the Union speech, and spelled out the commitments that we would make to maintain steadily, even if we have to stand alone, the economic constraints, our absence of participation in the Olympics, and so forth. We are inducing—I think we'll have substantial success—other nations to join us in these restraints.” Jimmy Carter: "American Society of Newspaper Editors Remarks and a Question-and-Answer Session at the Society's Annual Convention." April 10, 1980

I want you to consider one final point because it is interesting and insightful. After the Moscow Games and on the eve of the 1980 Presidential Election, Carter claimed something of a victory over the Soviets:

“… there has been a great effect on the Soviet Union by the Olympic boycott and also by the interruption of grain sales to the Soviet Union. More than 50 other nations joined us in deciding not to send any athletes to Moscow at all, which was a major propaganda victory over the Soviet Union.” -- Jimmy Carter: "Corpus Christi, Texas Remarks and a Question-and-Answer Session at a Townhall Meeting." September 15, 1980.

This might be prudent campaigning, but I’m not so sure about the “great effect” part. The boycott didn’t seem to have much effect on the Soviet Union, at least not as far as their Afghani policy was concerned (the U.S.S.R. didn’t withdraw until 1988). And I doubt that the U.S.S.R. felt its prestige took much of a hit. The Soviets won a then-record 195 medals, 80 of them gold. If the Olympic Games are all about winning, maybe the Soviets were glad the Americans stayed home.

Source: Getty Images

The Effect

Now, the $64,000 question is: did Jimmy Carter’s strategy of going public work? Answering this question is a little trickier than it first appears. On one level, the answer is obvious: it worked because the U.S.O.C. boycotted the Games. At a deeper level, however, we must consider whether a) Carter effectively shaped public opinion, and b) if so, how much of that influenced the U.S.O.C.’s decision. In other words, did the U.S.O.C. boycott the Games because of Carter or for some other reason (e.g., perhaps they, too, felt attendance was inappropriate)?

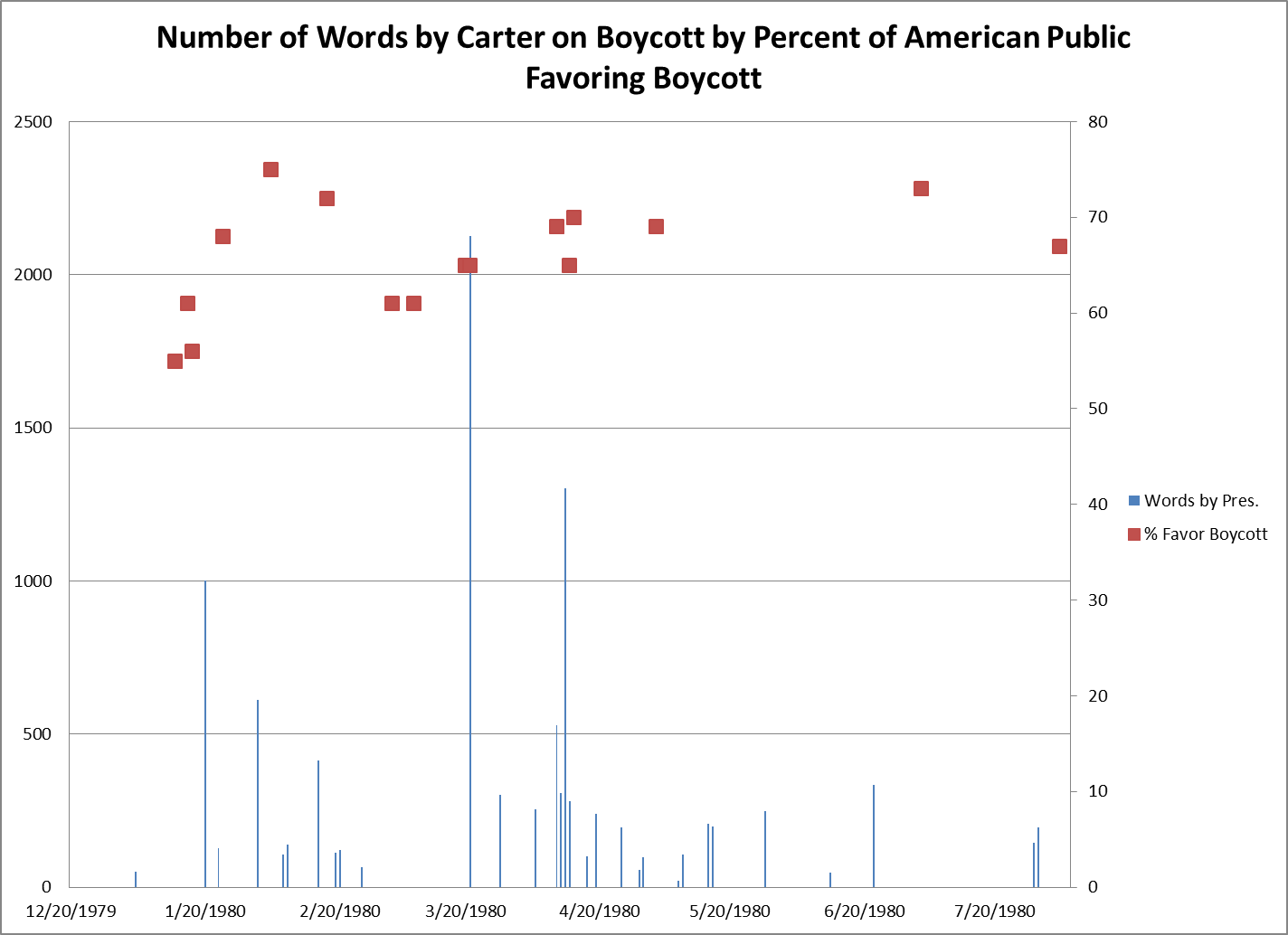

The chart below suggests Carter was able to move public opinion. The blue lines are the number of words Carter devoted to the boycott; the red squares are the percentage of Americans who favored a boycott.

Carter’s major statements on boycotting the Games came in his January 20th Meet the Press interview and, two days later, in his 1980 State of the Union Address. The percentage of Americans favoring a boycott went from the mid-50s before these statements to 75 percent after. A shift of 20 percent is remarkable. And while support slid shortly thereafter, it did rebound to the high-60 percent range the days before the USOC held its vote. It seems the first leg of Carter’s going public strategy—moving public opinion—worked.

Although I conclude that Carter’s rhetoric moved public opinion, I note three caveats. First, people other than Carter were talking about a potential boycott during this time, so it is impossible to know how much of a shift in public opinion was due to the president. Second, the first public opinion poll was taken after Carter’s first discussion of a boycott, so we can’t see what opinion might have been without a White House statement. Finally, Americans supported a boycott before Carter gave his most important speeches, so they didn’t need a lot of convincing from the White House. Despite these objections, I think the most likely reading of the evidence suggests that Carter rallied public support for a boycott.

As we have learned about going public, moving mass opinion is all for naught if policy doesn’t follow. Fortunately for Carter, but unfortunately for the American athletes, it did. On April 12, 1980, the U.S.O.C. voted to boycott the Olympic Games.

We cannot say it was Carter’s going public strategy alone that dictated the outcome of the USOC’s vote. Maybe it was the behind-the-scenes lobbying by the Carter administration that mattered. Maybe it was the near-universal calls from the press to boycott the Games. Maybe it was the nonbinding resolutions supporting a boycott passed by Congress in late January (386-12 in the House; 88-4 in the Senate). Or, maybe USOC members decided on their own that a boycott was a good idea.

However, two reasons suggest that USOC members felt enough pressure from the White House and the American people to boycott the Games despite personal objections. The first is that they said as much. One U.S.O.C. member put it, “I feel I have no choice but to support the president or be perceived as supporting the Russians. I resent that.” The second reason is counterfactual. If Carter had never mentioned a boycott, would it still have happened? I doubt it. Most of the USOC members seemed inclined to go to Moscow in January, but two months later, they did an about-face and voted for a boycott. Something must have happened in the interim, which was most likely Carter’s going public.

Source: https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2014/02/carter-olympic-boycott-1980-103308/

The Two Presidencies Thesis

Why did Carter succeed in going public when so many other presidents have failed? More specifically for our purposes, why was Carter able to go public on sports when both Clinton and Bush failed? Consider some standard political science reasons behind why some rhetorical efforts work and others do not:

More popular presidents should have an easier time going public. But Carter wasn’t popular. When these presidents went public, Clinton and Bush’s popularity hovered in the low-50 percent range, while Carter’s was in the 30s.

Presidents who are gifted public speakers should have an easier time going public. But Carter wasn’t a skilled orator—a 2017 CSPAN survey of presidents’ ability at public persuasion ranked Clinton 9th, G.W. Bush 25th, and Carter 35th.

So how is it that an unpopular president who wasn’t much of a public speaker could convince a sports-crazed nation that boycotting an Olympic Games was a good idea?

The answer is that Carter was dealing with an international crisis, while Clinton and Bush were dealing with domestic issues. Political scientist Aaron Wildavsky was the first to note what is called the two presidencies thesis: presidents tend to be more powerful in foreign policy than domestic policy. There are a number of reasons for this, but one is the tendency of the American public to rally around the flag (and the president) during times of international crisis. Political opposition is usually muted during crises, the press tends to support the president, and politics seem to stop at the water’s edge. Simply put, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan was a much bigger deal than either a baseball strike or steroids in sports. As a result, Carter was able to move public opinion and get the policy he desired.

The broader lesson here is that presidents have an easier time going public on foreign policy. I’m of the going-public-usually-doesn’t-work school of thought. But, three exceptions I can think of all involve foreign policy:

Harry Truman’s 1947 announcement of the Truman Doctrine before a joint session of Congress kicked off the Cold War. Almost overnight, the American public went from being isolationist and thinking the Soviets were our allies to interventionists and thinking the Soviets were our mortal enemy.

The Bush administration’s case for war in Iraq, made from 2002 to 2003, where the percentage of Americans favoring war went from 52 percent in August 2002 to 72 percent in March 2003.

Carter and the 1980 Moscow Boycott.