Introduction to the politics of sports

The Box Score

Politics affect the sports we watch and play. Consider a few examples:

Congress allows sports leagues to blackout games.

The Supreme Court ruled that walking is not an integral part of golf.

Presidents have issued executive orders that either barred or allowed transgender athletes.

Sports affect our politics. Athletes use their fame to become politicians. They bring attention to social issues, like the fight for racial and gender equality. And our love of sports affects how we spend billions of our tax dollars.

The rules of the game matter. At their core, politics and sports are little more than a set of rules. Knowing these rules allows us to predict behavior. The easiest way to change things is by changing these rules.

The Complete Game

I was a redshirt freshman quarterback at Stanford University in the fall of 1990. Life on The Farm was different from my days at Corvallis (OR) High School. The players were bigger and faster. Classes were tougher. It didn't rain in Palo Alto. But one thing remained the same: I never took a drug test.

Every football coach in America starts off two-a-days with the same speech: "This is our time!" "We're going to outwork everyone!" “The only people that matter are in this room!” The ethical coaches—a much smaller subset—talk to their players about appropriate behavior: Treat women with respect. Go to class. Stay away from drugs and alcohol. Don’t do steroids.

Source: SI

Performance-enhancing drugs didn’t start with Mark McGuire or Lance Armstrong. The ancient Greeks ate animal testicles to gain a competitive edge. The Nazis, hoping to create a super-soldier, tested steroids on prisoners during WWII. The USSR and East Germany had sophisticated doping regimes as early as the 1950s. By the time Ben Johnson demolished the 100m record in the 1988 Seoul Games and Tony Mandarich appeared on the 1989 Sport Illustrated cover, we all had a good idea that steroids worked.

In 1986, the NCAA began drug testing teams that made it to the postseason. Testing all Division I football teams started in 1989, and, a year later, all D-1 athletes were subject to random drug tests.

As the 1990 season was drawing to a close, I realized that although my coaches told me not to do steroids, no one had bothered to check to see whether I listened. I asked one of the older players, what gives? Why no drug test?

“No drug tests for us,” he said. “Jennifer and Barry have an injunction.”

“An injection?”

“No, dumbass. An injunction.”

Jennifer was Jennifer Hill, co-captain of the women’s soccer team; Barry was Stanford linebacker Barry McKeever. Along with dozens of other Stanford athletes, Jennifer and Barry were co-plaintiffs in a suit—Hill v. NCAA—that contended drug testing violated their right to privacy under Article I, Section I of the California Constitution. They had a point. Having a stranger watch you pee does seem like an invasion of privacy. (And this is not just some disinterested NCAA monitor watching your back as you are at the urinal. NCAA representatives watch the urine come out of your urethra to make sure you don’t pull the ole sample switcheroo.)

The Cardinal athletes also argued that the NCAA’s list of over 3,000 banned substances was absurd. Banned substances included over-the-counter drugs like Sudafed, Vicks cough syrup, and Wyanoids Hemorrhoid Suppositories. The NCAA also banned ingredients commonly found in herbal tea, coffee, Coke, and birth control pills. God help you if it was drug testing time and you woke up early for an 8 am class with a cough and a case of bum grapes.

A California trial court initially ruled in favor of Hill et al., which prevented the NCAA from drug testing Stanford student-athletes. The injunction only applied to Stanford University; every other Division I program had to comply with the NCAA’s drug-testing rules. It pays to be smart and litigious.

The NCAA then appealed to the California Supreme Court. In 1994, that Court reversed, ruling that student-athletes have a diminished right to privacy. Drug testing finally arrived at The Farm, but I graduated without a drop of my piss going to a lab.

The Stanford drug-testing case piqued my interest in the intersection between politics and sports for several reasons. The case affected me, so I paid more attention than usual. But more importantly, I thought drug testing student-athletes raised interesting ethical and political questions. Does protecting the integrity of athletic competition outweigh athletes’ right to privacy? And who’s to say? The NCAA? The California Supreme Court? The U.S. Supreme Court? (Incidentally, the mid-1990s were not kind to the civil-libertarian-student-athlete. Around the time the CA Supreme Court ruled against Hill et al., the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that testing high school athletes for recreational drugs did not violate the Fourth Amendment’s prohibition against unreasonable search and seizures.)

I was, and, in many ways, still am, conflicted about drug testing student-athletes. If there is any right to privacy in America, it surely includes the right to pee in private. And college athletes are busy people who cannot afford to consult the NCAA’s fifty-six-page list of banned substances every time they have a runny nose. On the other hand, I favor clean sports and have no respect for those whose on-field success comes through better off-field chemistry. Despite my ambivalence about drug testing, I became certain that politics played a significant role in the way we watch and play sports.

22ZIN uncovers the myriad ways that sport intersects with politics. To do so, we’ll explore three major themes:

#1. Politics Affects Sport,

#2. Sport Affects Politics,

#3. The Rules of the Game Matter.

I’ll briefly introduce each theme here and unpack them throughout the website.

#1. Politics Affects Sport

Politics is the last thing most of us want to think about when we flip on a Sunday afternoon game. Indeed, many of us watch sports because we either need a break from politics or hate politics altogether. But politics are inescapable, even during a little Sunday afternoon escapism.

Ever turn on the television to watch your local MLB team only to find the game blacked out? You can blame Congress’s Sports Broadcasting Act of 1961 for that, and for the remote you smashed when you found out the game wasn’t on. Grateful that so many girls and women have the opportunity to play sports? Thank Congress for Title IX of the Education Amendments Act of 1972. Want to lay a C-note on Duke (+3.5) over North Carolina but don’t want to go to jail for placing an illegal bet with some shady bookie? The Supreme Court’s 2018 decision in Murphy v. the NCAA now allows you to bet on sports in most states. In short, politics has a significant but underappreciated effect on the sports we watch and play.

Before we get too deep into how politics affects the ballgame, let’s get a few questions out of the way.

#1. What gives the government the right to interfere with sports? I’ve read the Constitution. There is nothing in Article I that says Congress can regulate NFL broadcasts. Nothing in Article II told President Lyndon Johnson he could doom generations of American schoolchildren to the public humiliation of the Presidential Physical Fitness Test. And nothing in Article III says the Supreme Court gets to decide whether walking is an essential part of golf.

When the Framers wrote the Constitution in 1787, “sport” meant killing some animal; it never occurred to them that, someday, sports might become a matter of public concern. So, how did we get to the point where we need a Political Science 101 refresher course just to read the sports page?

The right of the federal government to get involved in sports boils down to two things: money and vagueness. American sports bring in a lot of money; by one estimate, the entire U.S. sports industry generated almost $500 billion in 2015. And when money is involved, so too is the federal government. The Constitution gives Congress the right to regulate interstate commerce, the executive branch carries out these regulations, and federal courts arbitrate disputes between economic parties. In short, the Feds have a say in sports because (a) there is a lot of money involved, (b) teams cross state lines to play games, and, therefore, (c) sports are subject to governmental regulation like any other industry. (Interestingly, throughout most of the 20th Century, the federal government did not consider sports interstate commerce. We’ll take up the curious case of sports’ antitrust immunity in Curt Flood, The Supreme Court, and Baseball’s Antitrust Exemption.)

The second reason for the federal government’s involvement in sports is that the U.S. Constitution is vague. Imprecise language—such as “general welfare,” “necessary and proper,” “take care,” or “executive power”—gives politicians a lot of wiggle room. This wiggle room has enabled Joe Biden to protect transgender athletes via Executive Order. It allowed Congress to debate when a concussed athlete could return to the field. And it provided the basis for the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court to render judgment on Tom Brady’s deflated balls. In short, the federal government uses the murkier waters of the U.S. Constitution to wade into the controversies of the sporting world.

#2. Don’t politicians have more important things to do than worry about sports? Of course they do. No politician is crazy enough to argue that sports are more important than issues like COVID-19, inflation, or the war in Ukraine. However, the federal government is enormous and can do many things simultaneously. So, when Congress holds hearings on steroids in baseball, that does not mean they have forgotten about the federal debt. It is also within the government’s purview to address public health concerns in sports, including steroid abuse and head trauma. And politics reflects the broader culture. It would be odd, for instance, if a president refused to participate in those most sacred rituals of American civil religion: Super Bowl Sunday, the World Series, or March Madness.

Are there more important things in the world than sports? Absolutely. Does that mean the American government should stay on the sidelines when there are problems in the sporting world? Well, that depends…

#3. Doesn’t politics corrupt the sports we love? In future posts, we will see that most Americans prefer the government to stay out of the ballgame. There are many reasons behind this sentiment, the biggest is the widely held myth that sports are pure while politics are corrupt. This is sentimental nonsense.

There are many cases where sports leagues are unwilling or unable to put their houses in order. In these cases, governmental intervention is one of the few things that can save sports from themselves. For instance, boxing and horseracing would be even more corrupt without political intervention. MLB dugouts would have bowls full of greenies and syringes of Dianabol for the players, alongside sunflower seeds, Bazooka bubble gum, and tins of Copenhagen. And the NFL would continue to insist that football is no more harmful to their players’ brains than playing golf. Although governmental intervention should be a last resort, it is often the last stop on sports’ road to perdition.

There are times, however, when politics make things worse. For example, we’ll examine tax-payer-funded stadiums, one of the all-time great examples of corporate welfare. Or consider how Donald Trump’s numerous Tweets about the NFL players’ national anthem protests divided an already divided America. And, sometimes, politicians with good intentions still manage to screw things up. We’ll examine how Bill Clinton and George W. Bush respectively bungled the 1994-95 MLB strike and baseball’s steroid scandal in the early 2000s.

No one bats a thousand. However, the American government has a decent average in dealing with problems in the sporting world. Politicians typically address the sports-related issues that need addressing and usually succeed in making things marginally better. (The “marginally” part is important here. As we’ll see, the U.S. government doesn’t hit many home runs, but it does get on base.)

My research shows that while there is a lot of political bluster surrounding sports, the government seldom follows through with new laws or regulations. But actual legislation is rarely the important thing. Instead, the threat of government intervention is usually enough to convince sports governing bodies to clean up their act (see A Useful Threat). The American government is a lot like Barry Bonds in that respect. Bonds was great not just because of the record number of home runs he hit but also for those he might have hit. Just as Bonds’ power meant that pitchers took his threat seriously—he is MLB’s all-time leader in walks—the American government’s power means that sports governing bodies must take politicians’ threats seriously.

#2. Sports Affects Politics

The causal arrow between sports and politics runs both ways:

Politics —> Sports

Sports —> Politics

22ZIN explores how sports influence our political system, including who we elect, how we view ourselves and others, and what we pay for with our tax dollars.

Athletes in American Elections. As I show in “Athletes in U.S. Elections,” being a famous athlete is a great way to jumpstart a political career. Ex-jocks don’t need political experience to win elections. They don’t even need to know that much about politics. All they have to do is to remind voters that they were, say, a Hall of Fame pitcher for the Detroit Tigers, and suddenly, it is Senator Jim Bunning. Okay, winning elections is not quite that easy, but it is close.

Social Issues. The privileged place of sports in American society means that the social dynamics extend far beyond the court, the field, the pitch, or the diamond. Perhaps sports' most significant contribution to the American political landscape is reflecting, and sometimes shaping, the world around us.

Nowhere is the constitutive effect of sports more apparent than issues of race. Segregated sports certainly reflected America in the first half of the 20th Century. Today, America confronts systemic racism through the NFL national anthem protests and the Brian Flores lawsuit. But, as we will see, sports can also be an instrument of progressive social change.

Sports also play a critical role in the struggle for gender equality. We’ll examine how Title IX opened the world of sports for millions of women and girls. But the struggle for equity continues in the fight for equal pay for U.S. national soccer teams and the facilities of the NCAA Men’s and Women’s Basketball Tournaments. We’ll also explore the controversy surrounding transgender Penn swimmer Lia Thomas and what her case says about the American culture wars.

Publicly-Funded Sports Stadiums. Do you ever wonder why your hotel tax is so outrageously high when you travel to a large American city? The chances are the city is using you to help finance their beautiful new stadium. Welcome to Cleveland!

There are a lot of tax-related sports boondoggles out there, but publically-funded sports stadiums take the cake. For the past century, American taxpayers have paid billions to build stadiums they’ll never visit. This corporate welfare has enriched billionaire owners at the expense of virtually everyone else. The American love affair with sports means we consider them public goods, on par with roads, bridges, and police.

#3. The Rules of the Game Matter

It may sound strange, but, in essence, politics and sports are little more than a set of rules. If there weren’t any rules, or if those rules were arbitrary, then neither democratic politics nor sports would be possible. Think back to your schoolyard games, where rules were capricious and self-serving:

“That’s a touchdown!” says Cary Flannigan.

“No!” yells Andy Jamison. “The end zone is the tree, not the rock.”

“The end zone was the rock when you had the ball,” Cary points out.

“No, it wasn’t!”

“Yes, it was!”

And, soon, the punching begins.

The same is true with democratic politics. In dictatorships, the few rules that exist don’t matter. Democracies, however, play by a reliable set of rules that determine who wins and loses. At least, they should.

We’ll spend considerable time on the matter of rules and why they matter, but for now, let’s briefly consider three crucial rules about rules that apply to both sports and politics.

Rule #1. Rules matter. I’m an institutionalist, which means I believe that individuals, groups, and institutions generally behave as they are incentivized to behave. This means behavior is largely predictable if we know (1) the rules and (2) the context.

Consider how rules matter in sports. Imagine that your basketball team is down by five points with twenty seconds remaining in the game and no timeouts. The other team inbounds the ball to their point guard, who begins dribbling out the clock. What do you do?

Given the context of the game and the rules governing basketball, you foul. It doesn’t matter if you’re the Berney Elementary Bulldogs or the Golden State Warriors; any rational team in that situation does the same thing. Perhaps 80 to 90 percent of sports are predictable in this way. Of course, sports are wonderful for the 10 to 20 percent that isn’t predictable.

The same goes for politics. Imagine that we will bet on whether the next bill introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives becomes public law. We don’t know who wrote the bill, what the bill does, or how much support that bill might have in the chamber. None of that matters. I would wager my entire life savings, which, admittedly, is not much, that the bill does not become law. Why?

I know the rules by which a bill becomes law in America. Those rules make it much easier to play defense than to play offense. If you are of a certain age, that little boy from Schoolhouse Rock taught you all you need to know when he lamented, “You sure gotta climb a lot of steps to get to the Capitol Building here in Washington.”

Consider the steps in the standard how-a-bill-becomes-a-law process below. If you want a bill to pass, you have to win at every stage; if you don’t want a bill to pass, you need just one stop.

Bill put on House subcommittee agenda

Bill voted favorably by the House subcommittee

Bill put on full House committee agenda

Bill voted favorably by the full House committee

Bill put on House Rules Committee agenda

Bill is given a favorable Rule by House Rules Committee

Bill put on the House floor schedule

Bill passed by House floor

Bill put on Senate subcommittee agenda

Bill voted favorably by the Senate subcommittee

Bill put on full Senate committee agenda

Bill voted favorably by the full Senate committee

Bill brought to the Senate floor by unanimous consent agreement

Bill overcomes a Senate filibuster

Bill passed by Senate floor

Different House and Senate versions of the same bill are reconciled

Both chambers have an up-or-down vote on the reconciled bill

The president signs the bill. If he vetoes it, then…

Bill has to be overridden by both chambers of Congress with a 2/3rds vote.

This process must be completed within two years of a congressional term; otherwise, the bill dies.

Theoretically, these rules should make it difficult to pass a bill. Empirically, only around 4 percent of bills become law; more recently, that figure has dropped to 1 or 2 percent.

Now, there are a lot of secondary factors that might lead me to slightly revise the odds, including…

Bills introduced by members of the majority party have a much better chance of passing.

Bills introduced early or late in the legislative calendar have a better chance of passing.

Omnibus appropriations bills have a better chance of passing.

Bills considered under budget reconciliation have a better chance of passing.

Bills dealing with a national emergency have a better chance of passing.

Bills that no one cares about—renaming a post office, for example—have a better chance of passing.

And so on…

But these factors are just small potatoes compared to the reality that it is really, really hard for any bill to become law in America. If there is any such thing as a sure bet, it would be that the next bill thrown into the Hopper dies in committee.

22ZIN examines the ways that the rules matter in both sports and politics. Among other things, we’ll see that:

Congress’s bark on sports is worse than its bite.

Presidents have less impact on sports than the legislative or judicial branches.

The Courts have profoundly shaped how we watch, play, and bet on sports.

Rule #2: Rules are never neutral. Be it politics or sports, the rules of the game are never neutral; they always benefit someone, something, or some strategy. That does not mean rules are necessarily unfair: bias and fairness are two different things. For now, let’s get a feel for how rules create bias.

I love the Olympic Games because I get to watch unfamiliar sports, including the snowboarding halfpipe (I’m a skier). In the Men’s Halfpipe finals at the 2022 Beijing Games, Japan’s Ayumu Hirano took a tumble on his first of three runs and scored a 33.75. On his second run, he performed a never-before-seen trick that, inexplicably (at least to me), only received a 91.75 from the judges, putting him in second place. In his final run, he received a gold medal score of 96.

I was mesmerized, but a little confused. I thought that the winner of the Olympic Halfpipe was the rider with the highest average on all three runs. If that were the case, Hirano would have been out of the running when he fell on his first run. I eventually realized that’s not how things work. In reality, the halfpipe rules state that each athlete gets three runs in the finals. Six judges rank those runs on a scale from 0 to 100, with the high and low scores thrown out. The competitor with the highest overall score on any run wins the gold. Hirano was better than his competitors on that final run and took home the gold.

Imagine how things would be different with different halfpipe rules. An alternative set of rules, like the ones that I initially thought governed the sport, might award the gold medal to the athlete with the highest average over three runs wins the gold. Under these rules, we would expect riders to play it safe on each run because a fall means you’re off the medal stand. In Beijing, Australia’s Valentino Guseli would have won gold under this system because he was the most consistent rider and one of the few who didn’t fall (Run 1: 75.75; Run 2 79.75; Run 3: 79.75). You can compare the actual gold medal stand at the 2022 Bejing Games with the alternative ranking:

The actual rules of the halfpipe reward riders for one big run. As a result, there is a strong incentive to take risks and go big. And because of these rules, there is a lot of falling—44 percent of the final runs in the Beijing Games scored less than 50 points.

While there is nothing necessarily “fair” or “unfair” about the actual rules for the Olympic halfpipe, they do privilege certain strategies and affect outcomes. The best-of-three rule incentivizes risk-taking and big moves. It narrows the field of gold medal hopefuls to those few athletes who can pull off the latest big move, like a triple cork (several tried, but only Hirano landed one). And they work against those steady-Eddy snowboarders, who don’t fall but don’t go big.

The same goes for politics. Let’s briefly consider the Electoral College to see how this works. Here are the basic rules:

Each state’s electoral votes equals its number of Senators (every state has two) and U.S. Representatives (one for small states, like Wyoming; 52 for California).

Most states award all their electoral votes to the candidate who receives the most votes within that state.

There are 538 votes in the Electoral College; it takes 270 votes to win.

These Electoral College rules make some behavior and outcomes more or less likely, including…

The election will come down to a few battleground states, like Florida and Pennsylvania. Candidates will campaign in these states and ignore the rest of the country.

The winner of the popular vote might not become president. This benefits Republican candidates (George W. Bush in 2000 and Donald Trump in 2016).

Now, consider an alternative reality where America elects presidents by a nationwide plurality. The rules would be much more straightforward:

There is a national vote for president.

The candidate with the most votes wins.

How might behavior and outcomes change in this new system? At a minimum, we should expect:

Candidates will campaign where the votes are, and “battleground states” would be a thing of the past. Republican candidates would spend time in Orange County, California, Democrats would campaign in Houston.

Republicans would have a more challenging time winning the presidency. If a nationwide plurality system had been in place, the GOP would have just one win in the past 20 years.

“Snowboarding and presidential elections are a lot alike” is a phrase you won’t read anywhere else. But both endeavors show us that (a) rules matter and (b) those rules are not neutral. This leads us to our final point…

Rule #3. The easiest way to change behavior and outcomes is to change rules. There are three options if we don’t like the way things are and want to make a change…

1. Change people

2. Change mindsets

3. Change rules

I discuss these options elsewhere, but let me give you my quick take:

1. Change people. This is our go-to option if we have the power. We fire the underperforming employee. We vote out politicians. We bench that bust of a quarterback. We divorce our spouses. The problem with changing people is that we usually put the new people into the same crappy situation that the old people were in. For some reason, we are surprised when the new person turns out to be just as bad as the old person.

2. Change mindsets. Maybe we can convince people to change. Americans are enamored with heroic leadership, where some coach, president, or teacher inspires us to do things we never thought possible. We love the Ted Lassos, Teddy Roosevelts, and Jaime Escalantes of this world. But exceptional leadership is just that, exceptional. Unfortunately, the rule is that getting people to change their mindset is borderline impossible.

3. Change rules. This is the easiest and most effective way to change behavior and outcomes. Consider the following from the world of sports and politics.

Changing the Rules (Sports Edition)

Don’t like big men like George Mikan and Wilt Chamberlain dominating the game? Widen the key.

Want more offense? Add a three-point line.

Want less offense? Raise the mound and deaden the ball.

Want a less arbitrary way of determining a national champion? Have a college football playoff.

Want a fairer game? Test for steroids.

Speed up the game? Add a shot clock

Changing the Rules (Politics Edition)

Don’t like the filibuster holding up your judicial nominations? Get rid of the judicial filibuster.

Don’t like committee chairs holding up legislation? Get rid of the seniority system.

Want to vote for the U.S. Senate? Pass the 17th Amendment.

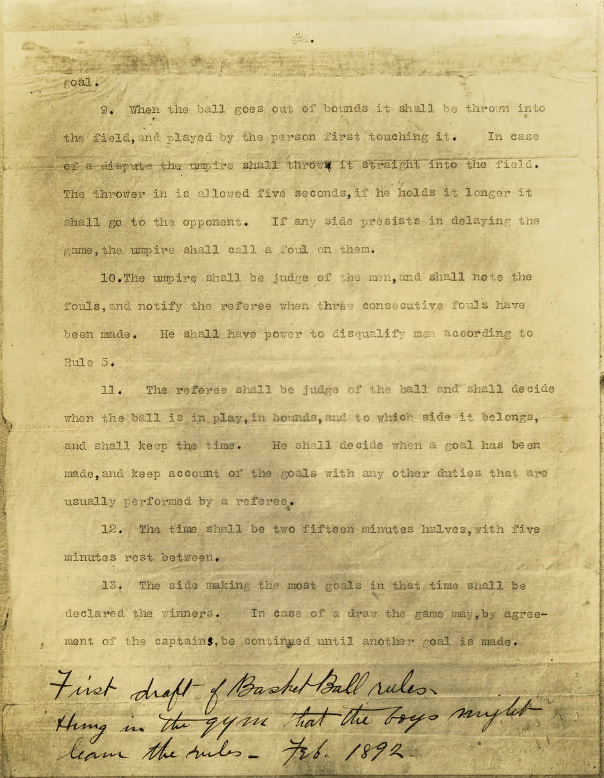

I want to point out a couple of things. First, it was much easier to develop a list of rules changes in sports than for politics. Consider the difference between Dr. Naismith’s 13 Rules of Basketball, which fits on two pages, and the Official Rules of the NBA, 2016-17, a stultifying 68 pages of single-spaced, 9-point font. Because of these changes, basketball looks quite different now than at the turn of the 20th Century.

Dr. James Naismith's Rules of Basketball. Source: https://debrucecenter.ku.edu/rules

There haven’t been nearly as many rule changes in American politics. Since the ratification of the Constitution, there have only been 27 amendments. Times have changed, but we’re still operating under essentially the same rule book that was written in 1789.

Second, it’s harder to change political rules than the rules of sports. Amending the Constitution is a really, really difficult process. It is even more challenging because powerful interests have an incentive for keeping things the way they are. Changing the rules of sports is no picnic either, but it is easier.

Resistance to change is more than navigating a complex process; it is about overcoming a collective mindset. Some sports purists resist any change. But whether we recognize it or not, most Americans are political purists, and fanatical ones at that. We’ve been taught from an early age to reify the Constitution and deify the Founders. We learn these lessons so well that, for most Americans, the Constitution is sacrosanct and to question it is downright un-American. This is a mistake and a misreading of American history.

Third, our unwillingness or inability to change the rules might be our downfall. We can point to boxing and baseball as sports that lost fans as they stubbornly resisted change. My concern is more political. As I argue elsewhere, the U.S. Constitutional system is premised on compromise. This system works when there is a healthy political middle of lawmakers and citizens willing to compromise (e.g., the textbook era of Congress, 1945-1979). The system does not work in periods of hyperpolarization when no one is willing to budge (1980s-Present). So, what do we do?

Option #1. Throw out incumbents and elect new people. This is most people’s go-to solution, but, really, all we’re doing is replacing bodies.

Option #2. Convince people not to be so polarized. Good luck! Pandora’s Box of polarization has been opened, and unless we get rid of social media and cable television, there is no closing it. That leaves…

Option #3. Change the Rules. The United States must, somehow, change its rules to cope with our new, polarized reality. Among other things, this means getting rid of the separation of powers and checks and balances, scrapping the U.S. Senate, and untethering congressional representation from geography.

Let me guess what you’re thinking. If you weren’t convinced before, now you are certain that I’m an idiot. You’re mad and are looking for the comments section to tell me so, which is why I don’t have a comments section. And you’ve completely shut yourself off to the possibility that America might be great in spite of her governing rules, not because of them. See, I told you that you are a purist!

But I think the most American thing we can do is put a critical eye on our governing documents and change them when necessary. That’s what the Founders had in mind when they wrote the thing. They didn’t think they were infallible, nor did they think the document they produced was perfect. So, I ask you to do the most American thing possible and consider in good faith whether our Constitution still works.

Thank you for reading. If you have any questions or comments, please contact me at tom@22zin.com.