Academics are Fearless! Mass and Elite Opinion in American Foreign Policy.

Surveys show that college professors are the bravest people in America. Okay, that’s not the point of this article, but it is a point of personal pride.

Instead, the point of this article is to answer the question: Does the average American think differently about foreign policy than “opinion leaders”? Since 1974, the Chicago Council on Global Affairs (CCGA) has conducted surveys that compare the foreign policy views of the general public with opinion leaders from the American government, media, business, think tanks, religion, and academia. [Note: I use “opinion leaders” and “elites” interchangeably.] The data visualization below shows the similarities and differences between elite and mass opinion in 2014.

Before we get to the data, let’s consider two questions to guide our thinking.

First, why should we care what “elites” think? One reason to care is that elites are the ones making policy. If policy elites think and act differently than the rest of us, it raises difficult questions about what it means to live in a democracy.

We should also care about what “elites” think because they are the experts. Elsewhere, I discuss how the strong anti-elite, anti-intellectual, anti-expert strain in contemporary American politics has disastrous consequences (see I’m in Waste Management and We Don’t Know What We’re Talking About). There are many examples of this, but for now, let’s consider the case of climate change.

In 2015, the American public thought there was roughly a 55-45% split within the scientific community over anthropogenic (human-made) climate change. The reality is that 97% of scientists believe humans cause climate change. A study by Sander van der Linden and colleagues found that people who accurately perceived the scientific consensus were far more concerned about climate change and willing to do something about it. Not surprisingly, the people who overestimated the scholarly divide were less concerned about climate change and far less willing to do something about it. The point here is that we ignore expert opinion at our peril.

Second, do elites and the public think differently about foreign policy? This seems an easy question to answer, but there is a surprising amount of scholarly debate about whether elites and the public think alike. Some scholars find a close link between Americans’ opinions and elite decisions (see Stimson, Mackuen, and Erikson’s “Dynamic Representation”). Others show that policymakers usually ignore the public (see Page and Bouton’s The Foreign Policy Dis*Connect).

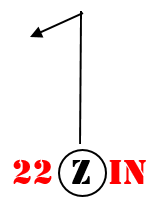

The following data visualization allows you to judge whether elites and the public are more alike than different. Use the radio buttons on the right to see opinions on questions pertinent to 2014. The red line shows the average opinion across all groups.

Have fun playing around with this data. When you are ready, read on to get my take.

Findings

Here are some findings that stuck out to me:

The American public is far more concerned with immigration than are elites (although the military runs a close second).

The American people, business groups, Congress, and the U.S. military are least likely to consider climate change a critical threat.

The American public, labor, and business groups are the most concerned about cheap foreign labor, protecting American jobs, and U.S. debt to China.

We shouldn’t think of “elites” as a monolithic group. The data viz shows considerable variation in how different elite groups see the world.

Academics ain’t scared of nothing! Well, that’s not entirely true: we’re scared of climate change. But beyond that, Academics are usually the least likely group to see things as “critical threats.”

Conclusion

The data paints a complex picture where the American public mirrors elites on some foreign policy issues but not others. Interestingly, the American public in 2014 presaged most of the major foreign policy trends that would come to define the past decade: anti-immigration, climate change skepticism, and a retreat from globalization. Of course, a data snapshot like the one provided above cannot fully unpack who is leading whom. However, it does suggest the American public was primed for a populist leader like Donald Trump.

There are two glaring questions left unanswered. First, how much have things changed since 2014? The CCGA has not released its most recent survey, and I am curious whether opinion has shifted and, if so, how much. Second, what is the relationship between elite and mass opinion? Do elites shape public opinion, or are opinion leaders kowtowing to the views of their constituents? These are interesting questions that I’ll try to address in a future post. For now, let’s all bask in the knowledge that academics are the bravest people of all.