You’re Voting Wrong

Telling folks that they are voting wrong is a good way to get a punch in the face. So, far be it from me to tell you which candidate to vote for; your vote is your business. But at the risk of a broken nose, I still bet you are voting wrong. The problem is not who you vote for—I don’t care whether you vote for Joe Biden, Donald Trump, or Lyndon LaRouche—but how you think about your vote. Whether we articulate it or not, we all have a philosophy of elections that determines whether we vote and whom we vote for. If you are like most Americans, you probably think elections are a selection process in which you use your vote to help bring about the desired outcome. This may sound like a perfectly reasonable definition of voting and elections, but it is spectacularly wrong.

If you think that you are participating in a selection process when you vote, then you implicitly believe that your single ballot can affect the outcome of an election. It won’t. Consider that there are two, and only two, situations when a single vote matters in a selection process: (1) if the vote creates a tie and (2) if the vote breaks a tie. All other votes pile onto an outcome that would have occurred with or without you.

In any decently sized election (say, above the level of a city council race), the probability that your vote will be decisive approximates zero. I once asked a mathematician friend to calculate the odds of being a decisive voter in a presidential election. He estimated it was .000000000000000000000000009%. “So you’re telling me there’s a chance.”

Still don’t believe me? Imagine what would have happened if you didn’t vote—or did vote—in the 2020 election. Would anything have changed?

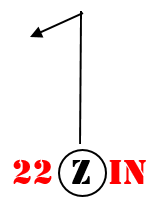

A single ballot has decided only 18 elections in American history, and most of those had under 5,000 voters. A back-of-the-envelope calculation is that there have been roughly 2,095,405 elections in U.S. history. That means you have a .0000009 percent chance of being a decisive voter, a figure close to my friend’s estimate. Simply put, you have a better chance of being struck by lightning on your way to the polling booth than your vote creating or breaking a tie.

The tendency of Americans to view elections as a selection process has many consequences, but here I will focus on two. First, it perpetuates the two-party system. The French political scientist Maurice Duverger noted that winner-take-all electoral systems, like the one we have in the U.S., tend to produce two viable political parties. That’s because people who like a minor party candidate usually cast a strategic vote for someone else. To illustrate strategic voting, consider Jane, a hypothetical voter who likes the Green Party. In the run-up to the 2020 presidential election, Jane reasoned that:

(a) although she is a big fan of Green Party candidate Howard Gresham Hawkins,

(b) she thinks Hawkins has no chance of winning the election.

(c) Jane doesn’t want to “waste” a vote on a hopeless cause.

(d) Therefore, Jane casts her ballot for the least objectionable major party candidate, Democrat Joe Biden.

Most erstwhile third-party voters behave like Jane. More than anything else, this weird quirk in voter psychology tightens the Democrats’ and Republicans’ grip on American politics.

A second consequence of viewing elections as a selection process is that our participation in politics is highly variable. We are simply more likely to vote when we think that doing so might affect the outcome of an election. For example, voting turnout tends to be higher in battleground states like Ohio (65% in 2012) and Florida (63%), and lower in non-competitive states like Texas (50%) or California (55%). And more people vote in elections that are expected to come down to the wire (55% nationwide in 1992) than in likely blowouts (49% in 1996). Perhaps most troubling of all is the individual variation in voting behavior that follows this line of thinking. The American National Election Study asked whether people agreed or disagreed with the following statement: “So many other people vote in the national elections that it doesn’t matter much to me whether I vote or not.” In 2000, only 32% of the people who agreed with the statement bothered to vote, while 84% of those who disagreed found their way to the polls. Unfortunately, voting when it “matters” means many Americans don’t vote.

The preceding argument may taste like a cold cup of coffee, especially coming from a political scientist who should encourage people to vote, not point out their insignificance. But there is an excellent alternative to the selection process philosophy of voting: the expressive model. The expressive model contends that we have a civic duty to vote. It reminds us that other Americans have fought and died for our right to vote. It also sees voting as our chance to register our opinion with the government and to suggest a future course if we don’t like the current one. In short, this view demands we vote because we ought to vote.

Here is the punch line: if voting is an act of expression rather than selection, voters should never cast a strategic ballot or abstain from voting. To cast a strategic ballot means, in essence, that voters are lying about their true political preference, which is an odd thing to do when expressing one’s preference is the only logical reason to vote. Simply put, you should vote for whomever you like because your single vote will not decide an election. Moreover, the expressive view of voting means that you must always vote. It doesn’t matter whether the next election promises to be razor-close or an absolute blowout, whether you are a Democrat living in Idaho or a Republican in Vermont, or whether you like Donald Trump or Gary Johnson. You should always vote, and you should always vote sincerely. In the expressive model, voting is a constant and is honest; in the selection model, voting is a variable and is somewhat dishonest.

For the record, I think that everyone should vote. But I also believe we should be clear on why we are voting and what we expect to get out of the act. Voting is a very important act of political expression, perhaps the most important, and requires citizens to give of themselves for the greater good. Our vote matters a lot. But I don’t believe I can decide the next election any more than I think I can win the next Powerball Lottery. So the next time you’re in the ballot box, take a page from Charles Wright’s funky 1970 hit and “Express Yourself.”