The Sports Talk Presidency

The Box Score

1. Presidents talk a lot about sports. Modern presidents talk about sports twice as often as they do the Supreme Court (4,549 sporting mentions vs. 2,256 Supreme Court mentions).

2. There are different types of presidential sports talk:

Instrumental: the use of rhetoric for a specific political purpose. For example, “I have notified the Olympic Committee that with Soviet invading forces in Afghanistan, neither the American people nor I will support sending an Olympic team to Moscow.” – Jimmy Carter’s 1980 State of the Union Address.

Constitutive: defining who we are as Americans. For example, “The United States of America was never meant to be a second-best nation. Like our Olympic athletes, this nation should set its sights on the stars and go for the gold” – Ronald Reagan, 1984.

Ingratiation: connecting with an audience. For example, “I understand that your [Kalamazoo, MI] boys' basketball team did pretty good. First State champions for the first time in 59 years. That didn't happen by accident. They put in work. They put in the effort.” – Barack Obama, 2010.

Analogies/metaphor: using sports to explain policy or shape opinion. For example, “You do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him to the starting line of a race and then say, ‘you are free to compete with all the others,’ and still justly believe that you have been completely fair.” – Lyndon Johnson, 1966.

3. Presidents mainly use sports to connect with an audience; they rarely politicize sports. Ingratiation is the most common feature of presidential sports talk (5,917 references), followed by sports analogies (2,247), constitutive rhetoric (2,185), and instrumental rhetoric (941).

4. Different presidents talk about sports in surprisingly similar ways. Presidents are remarkably similar in how often they use ingratiating, constitutive, analogies, and instrumental rhetoric. The similarity is not just quantity but quality. No matter their political party or temperament, most presidents sound the same when talking about sports. Trump is the exception.

The Complete Game

My research into how American presidents talk about sports began on March 14, 2012. That morning's SportsCenter featured ESPN basketball analyst Andy Katz discussing the upcoming NCAA men's basketball tournament with President Barack Obama. Obama opened with his theory of bracketology—pick teams with good end-of-season momentum and a solid point guard—before taking Katz round-by-round through his 2012 picks. Although Obama's bracket turned out to be nothing special, it was clear from the interview that he knew college hoops.

President Obama talking brackets with ESPN’s Andy Katz. Source

Watching Obama led me to think about other presidents. I did a quick mental scan of presidents since FDR and could easily recall how each had talked about sports, played a sport, were rabid fans, or made a decision impacting the sporting world. Eisenhower had a dreaded pine tree named after him at Augusta National. Nixon called Dolphins' Head Coach Don Shula the night before Super Bowl VI and told him to throw a slant to Paul Warfield. Ford was a former college football All-American at Michigan with a penchant for hitting spectators with golf balls and falling on the ski slopes. Carter boycotted the 1980 Moscow Games. George W. Bush owned the Texas Rangers and, three months after 9-11, threw out the first pitch in Game 3 at Yankee Stadium. And so on.

Although my top-of-the-head recollection suggested that presidents spend a lot of time on sports, a good social scientist never trusts these types of casual observations. I needed solid evidence to answer three questions on my mind:

Do presidents talk about sports as much as I think they do?

Why would presidents talk about sports?

How do presidents talk about sports?

That afternoon I embarked on a 10-year (really stupid and futile) journey to better understand how and why presidents talk about sports. Here's how I did it (for a full explanation of my methodology, see Methods):

I used over 100 sports-related terms to search the Public Papers of the Presidency for any presidential mention of sports. (Thanks to my UCSB friends John Woolley and Gerhard Peters for their excellent website The American Presidency Project).

That search yielded 4,549 speeches in which a president talked about athletics.

I then classified each mention into four categories of sports talk: instrumental, constitutive, ingratiation, and analogies.

Here's what I found:

1. Presidents talk a lot about sports

It wasn't just my imagination: presidents do talk a lot about sports. Figure 1 shows the dramatic rise of presidential sports talk. The modern sports talk presidency began with Nixon, who mentioned sports in twice as many speeches (137 speeches) as Johnson (67). The frequency of White House sports talk nearly doubled again under Gerald Ford (257) and, except for Carter, never dropped below 200 speeches per term for subsequent presidents. Obama talked more about sports than any other president (484 in his first term; 481 in his second), barely edging out Clinton (480 speeches in his first term). [NOTE: I've excluded Trump from this chart since I’ve only coded the first two years of his presidency].

Number of Presidential Speeches Mentioning Sports, Roosevelt to Obama.

White House sports talk has undoubtedly increased over the years, but that does not necessarily mean that recent presidents are any more sports-crazed than their predecessors. It may be that recent presidents are more loquacious in general, or that the Public Papers have somehow become more comprehensive over time. To compare presidents, I normed the data by dividing the number of documents a president mentioned sports by the total number of documents in that president's Public Papers. The normed data depicted in Figure 2 shows that, while the increase in presidential sports rhetoric is not as linear as Figure 1 suggests, recent presidents are more likely to talk about sports than their predecessors.

Percent of Presidential Speeches Mentioning Sports

I also counted the number of words presidents devoted to athletics over their term in office and then estimated the hours spent talking to the public about sports (assuming presidents talk at an average of 130 words per minute). Whether the 45-plus hours Obama spent talking about sports is a lot or a little is a judgment call, but it seems like a lot to me.

Number of Words, Minutes, and Hours Presidents Spend Talking about Sports.

Of course, presidents talk about many things, and maybe the amount of sports talk isn't so remarkable compared to other topics. To put presidential sports talk in some perspective, consider that President Obama talked about athletics (12% of his speeches) more than he said the words "terrorism" (10%), "Social Security" (5%), or "Canada" (3%). Ronald Reagan talked about sports far more than his Strategic Defense Initiative (5% sports; 3% Star Wars). Bill Clinton focused more on sports than on his impeachment (9% sports vs. 2% impeachment), perhaps for good reason. And George W. Bush talked about sports more than he mentioned Osama bin Laden (7% sports vs. 3% bin Laden). In fact, since 1900, twice as many documents in the Public Papers have mentioned sports (4,549) as have mentioned the Supreme Court (2,256).

Simply put, presidents love to talk about sports.

2. The uses of presidential sports talk

It may seem odd that presidents talk about sports at all. Presidents are busy people who face a long list of daunting problems, and surely sports must be near the bottom of that list in importance. At the most basic level, sports must matter to presidents, or they wouldn't talk about them so much. But, at a deeper level, presidents talk about sports because few subjects are as rhetorically useful or versatile. Sports are culturally relevant, linguistically evocative, and have the potential to unite people across political, racial, and class lines. Of course, American sports have never been the de-politicized, de-racialized, de-genderized, de-sexualized, de-commercialized, and meritocratic pastimes they are often made out to be. And ever since Colin Kaepernick first took a knee and Trump took to Twitter, sports have become just another front in the ever-widening partisan war. Still, on any given Sunday, fans of all stripes—Democrats and Republicans, Blacks and Whites, Christians and atheists, men and women, rich and poor—high-five and hug each other as their team scores the winning touchdown. This potentially unifying aspect of sports provides, or used to provide as the case may be, presidents with a valuable topic to communicate with an often divided American public.

Not all presidential sports talk is the same. It is helpful to think of four rhetorical strategies: 1. instrumental, 2. constitutive, 3. ingratiation, and 4. analogies/metaphors. These categories are not mutually exclusive, and their boundaries are often blurred. Still, this framework gives us a way to understand how and why presidents talk about sports.

Instrumental Rhetoric

Americans expect a lot from the White House, but presidents find themselves hamstrung by a constitutional system that separates power and gives Congress more of it (see Lesson #1 in “Five Lessons of the Modern Presidency”). Instrumental rhetoric is persuasion toward a specific policy end. There are many different forms of instrumental rhetoric, but here let’s consider two: going public and position-taking.

Going Public. Presidents usually go public with the ultimate objective of influencing Congress (for a fuller description of going public, see Lesson #3 in “Five Lessons…”). In sports, however, presidents usually go public to influence leagues or athletic governing bodies. I'll briefly discuss three presidential attempts at going public on sports here; you can find complete case studies in subsequent articles.

The most successful case of a president going public on sports was Jimmy Carter's boycott of the 1980 Moscow Games. Carter stated his intention to boycott the upcoming Moscow Games soon after the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in December 1979. Unfortunately for Carter, presidents have no legal authority to issue an Olympic boycott. That question is up to the United States Olympic Committee (USOC), and the USOC is a private organization.

Lacking any direct power, Carter had to convince the USOC not to send athletes to Moscow. Carter exerted pressure by calling for a boycott in 40 speeches, including in his 1980 State of the Union Address, "I have notified the Olympic Committee that, with Soviet invading forces in Afghanistan, neither the American people nor I will support sending an Olympic team to Moscow." Ultimately, the USOC agreed to the boycott, prompting one member to say, "I feel I have no choice but to support the president or be perceived as supporting the Russians. I resent that.”

Jimmy Carter embracing a would-be Olympian at the White House. Source

Other cases of presidents going public on sports didn't turn out so well. Bill Clinton’s attempt to settle the 1994-95 Major League Baseball strike is one example. In a January 1995 interview with NBC's Tom Brokaw, Clinton said:

"But there are people—there's still a significant percentage of the American people, probably you and I among them, who really believe baseball is something special. And you know, there's a few hundred owners and a few hundred more players, and baseball generates $2 billion worth of revenues every year; about a thousand people ought to be able to figure out how to divide that up and give baseball back to the American people, and I hope they'll do that."

Clinton ultimately struck out in his attempt to save baseball. He first appointed former Secretary of Labor Bill Usery as a "super mediator" and promised to "lock" MLB owners and player reps in the White House until they came to a deal. No dice; Strike 1. He then took his case to the American public in 15 separate speeches. Not only did Clinton fail to move public opinion, but 72 percent of baseball fans opposed his attempt to settle the strike. Strike 2. Finally, in what sports writer George Vecsey rightly called a "civics lesson," the White House watched another branch settle the strike when then-U.S. District Judge and now-Supreme Court Justice Sonya Sotomayor cited owners for unfair labor practices. Strike 3.

Southpaw President Bill Clinton Throwing Out the First Pitch. Source

A final example of a president going public on sports was George W. Bush's call for professional sports leagues to get rid of steroids. In his 2004 State of the Union Address, Bush stated:

"To help children make right choices, they need good examples. Athletics play such an important role in our society, but unfortunately, some in professional sports are not setting much of an example. The use of performance-enhancing drugs like steroids in baseball, football, and other sports is dangerous, and it sends the wrong message, that there are shortcuts to accomplishment and that performance is more important than character. So tonight I call on team owners, union representatives, coaches, and players to take the lead, to send the right signal, to get tough, and to get rid of steroids now."

A president talking about the evils of steroid abuse is usually no big deal. However, it is odd, maybe even inappropriate, to do so in the State of the Union Address, the most important speech a president gives all year. At best, it was politically tone-deaf to discuss steroids as the situation in Iraq deteriorated. At worst, critics charged that Bush was trying to divert the American public's attention away from more severe problems at home and abroad (call it a "wag the dog" strategy on steroids).

Bush ultimately accomplished little by talking about steroids in the SOTU: he didn't move public opinion or force the sports leagues to enact tougher PED policies. All Bush seemed to do was spend precious political capital on a topic that few felt worthy of attention.

Presidential Position-Taking. Position-taking is about sending political signals to an audience (see Lesson #3 in “Five Lessons…”). Since American sports enjoy large audiences, presidents often use them to send messages to bolster political support. For example, President Obama used NBA player Jason Collins's coming out as an occasion to state "that the LGBT community deserves full equality," thereby signaling his evolution on gay marriage. We might also consider Bill Clinton's comments in the wake of the Supreme Court's Santa Fe (1999) decision banning public prayer before a high school football game. Clinton disagreed with the Court's ruling in four separate statements, including this one:

"Now, it's [the separation of church and state] been carried to such an extent now where they say, some people have said you can't have a prayer at a graduation exercise. I personally didn't agree with that. Why? Because if you're praying at a graduation exercise or a sporting event, it's a big open air thing, and no one's being coerced. I'm just telling you what my personal opinion is. I can't rewrite the Supreme Court decisions." William J. Clinton: "Remarks in a Town Meeting in Charlotte, North Carolina," April 5, 1994.

Clinton was right in at least one respect: he couldn't rewrite the Supreme Court decision. So why publically disagree with the Court’s ruling? Well, 68% of the American public also disagreed with the Court's decision, and it is always good to be on the public's side.

But the mother of all presidential sports position-taking belongs to Donald Trump. During the 2016 NFL pre-season, San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick first sat, then, after consultation with former Seattle Seahawk player and ex-Green Beret Nate Boyer (who is White), eventually took a knee during the national anthem to protest police brutality and racial injustice in America. Other NFL players, almost all Black, soon took up the protest.

Kneeling during the national anthem was controversial before then-presidential candidate Donald Trump first weighed in on the subject on August 29, 2016—Trump said that Kaepernick "should find a country that works better for him"—but much like the birther movement, Trump became the reactionary ringleader.

Colin Kaepernick (right) and Eric Reid (left) kneeling during the playing of the national anthem before the 49ers game with the Panthers, September 18, 2016. Source

For Trump, kneeling had nothing to do with racial injustice; it was simply an affront to America, its symbols, and the U.S. military. "The issue of kneeling has nothing to do with race," the president said in a September 2017 tweet. "It is about respect for our Country, Flag, and National Anthem." Trump knew early on that the NFL protests offered him an issue that resonated with his base. At a dinner with conservative leaders in mid-September, Trump boasted that his critique of the NFL players was gaining traction. "It's really caught on. It's really caught on," the president bragged. "I said what millions of Americans were thinking." Soon, railing about kneeling Black NFL players became Trump's go-to issue whenever he needed to whip his audience into a frenzy.

Now, a case can be made that Trump's NFL comments are an example of "going public" rather than "position-taking." The difference between the two strategies is that going public has a policy goal, and position-taking has a political goal. In practice, the strategies often overlap, as they do here. To my thinking, Trump cared more about using the NFL to score political points, which suggests position-taking. In any event, Trump is the first president to fully embrace sports as a political wedge (See “Get That SOB Off the Field”).

Constitutive Rhetoric

Constitutive rhetoric attempts to carve an "imagined community” out of a diverse collection of people. If instrumental rhetoric is the attempt to win a political game, then constitutive rhetoric says who is on the team and sets the rules of the game.

Sports lend themselves to constitutive rhetoric perhaps more than any other subject. Sports transcend (or used to transcend) divisions in American society, which provides presidents a valuable subject to define the collective we. The constitutive power of sports is evident during global events, like the Olympics and the World Cup, where Team U.S.A. takes on the world. Presidents invariably use these international competitions to tell the American people who they are, who they are not, and who they should aspire to be.

Consider, for example, how three very different presidents (Reagan, Clinton, and Obama) offer essentially the same depiction of how the U.S. Olympic team reflects the proverbial American melting pot:

President Ronald Reagan with gold medal gymnast Mary Lou Retton after the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games. Source

Reagan: And I have just a final point here. One of the things I noted and liked so much as I watched the games on TV was that often in many of the events, you could sort out or figure out who represented what country, except with the American athletes. With the American athletes, we almost always had to see the U.S.A. on your uniforms, because our team came in all shapes and sizes, all colors and nationalities and races and ethnic groups. And I was thinking, you can talk on and read forever books about the melting pot; but the past 2 weeks, there it was winning medals for us, representing us every day—140 countries represented here in the only place in the world where those who are competing for this nation had the bloodlines and the background of more than those 140 countries.

Clinton: The last thing I want to say is this: If you look around in this vast, wonderful, magnificent sea of people, you will see people whose ancestors came from all different places. When I went to see the Olympics and to start them off and I met with the American Olympic team, it made chills run up and down my spine. I thought to myself, if these kids didn’t have the American uniform on and they were just walking out there in the Olympic Village, you wouldn’t have a clue where they were from. You’d think, well, that person is on the African team and that one’s on the Korean team and that one’s on the Japanese team and that one’s from the Caribbean somewhere and this one’s from Latin America and the other one’s from Europe and there’s somebody from Scandinavia. You can be from anywhere and be American.

Obama: And one of the great things about watching our Olympics is we are a portrait of what this country is all about: people from every walk of life, every background, every race, every faith. It sends a message to the world about what makes America special.

Sports and athletes also serve as a trope to highlight American values. Athletes are often held up as exemplars of the American character and praised for their hard work, dedication, perseverance, teamwork, and selflessness. Consider the following quotes:

“And I think one reason we like the Olympics is that everybody gets a chance, everybody plays by the rules, you don't get anywhere by badmouthing your opponent, you can't get a medal if you break your opponent's legs and break the rules. You just got to reach down deep and do the right thing. And even if you don't win, you're better off for having tried. That's the America I'm trying to build. That's the America I want you to have.” -- William J. Clinton: "Remarks at Michigan State University in East Lansing, Michigan," August 27, 1996

“And when you come to the Baseball Hall of Fame, part of what you're learning is that there is some eternal, timeless values of grit and determination and hard work and community and not giving up and working hard. Those are American values, just like baseball.” -- Barack Obama: "Remarks at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York," May 22, 2014

“I was struck by Tim Duncan's comments after the sixth game when they were talking about the fantastic individual effort he had. And a reporter said, "What about that effort?" He said, "It's cool," but then immediately went on to talk about the accomplishments of his teammates, recognizing that you can't win a championship unless you're able to rely upon others and lift others up and participate with others and work hard with others. And it's a phenomenal tribute to the San Antonio Spurs that they've got such great individual players who are willing to work as a team. And it's a wonderful example for our country—it really is.” -- George W. Bush: "Remarks Honoring the 2003 National Basketball Association Champion San Antonio Spurs," October 14, 2003.

Sports are easily co-opted for political purposes because they are popular, highly ritualized, and symbolic. The embedding of patriotic and militaristic symbols in American sports is so commonplace that it has become part of the game. We expect, for instance, that the national anthem will come before the start of a game; for major professional sports leagues to salute the troops; to see a military flyover before the Super Bowl or Rose Bowl; and, post-9/11, to sing God Bless America during the seventh-inning stretch. This confluence of sports and patriotism even helps define a political reality. It is instructive, for example, that the political debate surrounding the NFL protests has centered on whether players should stand for the anthem rather than the prior question of whether it is appropriate to play the national anthem before a game.

Ingratiating Rhetoric

We might consider this the Toastmasters’ rules of presidential rhetoric. Like all speechmakers, presidents need to connect with an audience. Establishing a rapport usually involves flattering the audience, telling jokes, and presenting a carefully crafted image.

Sports are tailor-made for such efforts. When presidents tour the country, they often begin their remarks by congratulating the local team on its accomplishments—the presidential equivalent of Spinal Tap’s “Hello Cleveland!” People go nuts for this sort of thing. Consider Barack Obama’s shout-out to the Kalamazoo Central boys’ basketball team in 2010:

“I understand that your [Kalamazoo, MI] boys’ basketball team did pretty good. First State champions for the first time in 59 years. That didn’t happen by accident. They put in work. They put in effort.” – Barack Obama, “Commencement Address at Kalamazoo Central High School in Kalamazoo.” June 7, 2010

The self-deprecating sports joke is a staple of presidential speeches. These jokes are usually the kind that people laugh at only because a president has told them, but they tend to be endearing and humanizing. Gerald Ford was the greatest practitioner of this technique. The starting center and MVP of the 1933 University of Michigan football team, Ford frequently remarked that he played football back when “the ball was round.” And Ford wove the same set of mildly amusing anecdotes into his speeches. Here is one example:

“Although, when it comes to personalized views, I don’t think I will ever forget the one expressed by a former teammate of mine from my old Michigan football team. He introduced me one time at a banquet and said, ‘You might be interested to know that I played football with Jerry Ford for 2 years. Jerry played center, I was the quarterback, and you might say it gave me a completely different view of the President.’” -- Gerald R. Ford, Remarks at a Reception for Members of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists. May 6, 1976

Gerald Ford on the slopes. Source

An avid golfer and skier, Ford was often lampooned for his foibles on the links and the slopes. As for his golf game, Ford once quipped, “I know I am getting better at golf because I am hitting fewer spectators.” As for his skiing, Ford said, “let’s just say I can ski for hours on end, and you know which end I am talking about.”

The American public wants contradictory things from our presidents. On the one hand, we want our presidents to be “a regular Joe,” someone we can share a beer with and talk football. One of the ways presidents can seem more relatable is to engage in fan talk. Talking about sports comes naturally to most presidents since they played sports or are genuine fans. And they’re usually insightful (whether they know what they’re talking about or have excellent advance work is hard to tell). Bill Clinton, for example, offered this trenchant analysis of Super Bowl XXXI between the Packers and Patriots:

“…the fact that they [the Packers] played a very tough NFC schedule and ranked first in offense and third in defense and they’ve got great wideouts and great tight ends and a good running program. You know, that’s a very rare thing to see that. I think that gives them a lot going. Now, the flip side is the New England team has come alive defensively in the last five games in a way that’s highly unusual… And it’s the one thing that makes me believe that—you know, the last several Super Bowls, the NFC team has won fairly handily. But if you look at the fact that the Patriots have a very skilled quarterback, a fabulous coach who is very savvy in circumstances like this… and been there before. And something happened, it was almost like a transformation of their defense in the last half dozen games of this year. I think you have to say that this could be the most interesting Super Bowl we’ve had in a long time.” -- William J. Clinton, Interview With Al Hunt of WBIS in Chicago, January 22, 1997

On the other hand, we want presidents to be better than us. We expect they have every fact at their fingertips, possess the Wisdom of Solomon, and speak eloquently without stumbling or stuttering. God help the president who screws up talking about sports. John Kerry, the 2004 Democratic nominee, serves as a cautionary tale. Kerry’s windsurfing was used in a 2004 Bush-Cheney advertisement as a ready-made visual for the flip-flopping claim. When Kerry was asked his favorite Red Sox player, the Massachusetts native replied, “Manny Ortez,” somehow conflating Manny Ramirez with David Ortiz and mangling Ortiz’s name in the process. Finally, Kerry mistakenly referred to the venerable Lambeau Field as Lambert Field.

A 2004 Bush campaign ad attacking John Kerry for being a flip-flopper.

Sitting presidents have also had their fair share of mistakes. At his remarks in Ames, Iowa, Jerry Ford stated, “It’s great to be in Ohio--Iowa State. [Laughter] You know we Michiganders have Ohio State on our mind.”

Ford was not the only president to temporarily forget where he was. George W. Bush, the all-time leader in presidential malaprops, made several eyebrow-raising statements over his two terms in office:

“And they brought home a national championship to the University of Wisconsin. Congratulations to you all. I mean, the University of Washington; I beg your pardon.” -- George W. Bush, Remarks Honoring NCAA Championship Teams April 6, 2006

“And then came the greatest sight of all--more than 500 America’s--of America’s finest athletes marching behind our flag, carried by Bernard Lagat [Lopez Lomong carried the flag].” -- George W. Bush, Remarks Honoring the 2008 United States Summer Olympic and Paralympic Teams, October 7, 2008

“In the weeks that followed, our Olympic team took part in the largest games ever held. Over 100,000 [10,000] athletes competed in more than 300 events.” -- George W. Bush, Remarks Honoring the 2008 United States Summer Olympic and Paralympic Teams, October 7, 2008

Sports can also backfire on presidents. Few presidential activities are more fraught with symbolic hazards than golf. Presidents have been criticized for golfing with business interests (Eisenhower and Ford), golfing at country clubs that refused to admit women or persons of color (Ford, Clinton, and Reagan), golfing during international crises (George H. W. Bush, George W. Bush, Obama, and Trump), or simply golfing too much (any president who dared to tee up a ball while in office).

“Now watch this drive…”

After George W. Bush addresses suicide bombing in Iraq, he tells reporters, “Now, watch this drive.”

Analogies

Metaphors and analogies play an essential role in political communication. In Poetics, Aristotle noted that “the greatest thing by far is to have a command of metaphor. This alone cannot be imparted by another; it is the mark of genius, for to make good metaphors implies an eye for resemblance.” Some analogies are instrumental, intended to shape opinions to accomplish political goals. When George H.W. Bush compared Saddam Hussein to Adolf Hitler in 1990, he essentially took a negotiated settlement off the table and began prepping the American public for war. Other presidential analogies are constitutive. For example, Professor of Rhetoric Alan Gross shows how Lincoln used two metaphors— “a nation is a living being,” and “a nation is a family”—to define what it meant to be an American during the Civil War. Presidents also use analogies and metaphors to explain policy and criticize political opponents.

Sports analogies and metaphors are ubiquitous. Scholars Palmatier and Ray identified more than 1,700 common sports metaphors in the American lexicon. Therefore, it is no surprise that presidents use a wide range of sporting analogies. Here are a few examples:

To discuss the values of the nation. Consider the following examples from Bill Clinton.

“And if you think about the Olympics, one of the reasons we love the Olympics is that people have to win on their own merits. They don't win by criticizing their opponents. Nobody can get a medal—no runner could win a medal by breaking his opponent's legs before the race. [Laughter] Nobody is more respected by telling everybody what a bad person his opponent is. In other words, in the Olympics people don't lift themselves up by putting other people down. They lift themselves up by bringing out the greatness that is within them. And that is what we should want for all Americans. We shouldn't want a single person in this country to be under the illusion that he or she is a better person because they're not of a certain race or they don't have a certain religious conviction or they happen to be born better off than someone else.”

“I think that America likes March Madness and likes college basketball as much as anything else because it is both an individual and a team sport. And it has both rules and creativity, discipline and energy. And in that sense, it is sort of a symbol of what's best about our country when things are going well. And I hope we can all remember that. We all need to live with rules and creativity, with discipline and energy, and we all need to remember that, however good any of us are, we're all on a team. And when we're on the team, the team's doing well, the rest of us, we do pretty well individually.”

“And I want to say also, though, you don't win three times in a row unless you have a team, unless everybody has a role to play and everybody plays it, and unless people understand that they all do better when they help each other. And that's the sort of spirit that we need more of, indeed, in more other teams in our country and in running our communities and our Nation.”

To discuss ideology. Sociologist Stephan Walk shows how Lyndon Johnson and Ronald Reagan used a footrace metaphor to communicate very different political philosophies.

LBJ. “You do not take a person, who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him to the starting line of a race and then say, ‘you are free to compete with all the others,’ and still justly believe that you have been completely fair.” – Lyndon Johnson, “To Fulfill These Rights” Commencement Address 1966

Reagan. “We offer equal opportunity at the starting line of life, but no compulsory tie for everyone at the finish.”

To rally public support for military action. In his 1998 State of the Union address, Clinton used a football analogy to justify a continued U.S. military presence in the Balkans:

“To take firm root, Bosnia's fragile peace still needs the support of American and allied troops when the current NATO mission ends in June. I think Senator Dole actually said it best. He said, ‘This is like being ahead in the fourth quarter of a football game. Now is not the time to walk off the field and forfeit the victory.’”

To explain political decisions. Barack Obama used a sports analogy to illustrate why his administration decided not to release pictures of a dead Osama bin Laden:

“You know, that's not who we are. You know, we don't trot out this stuff as trophies. You know, the fact of the matter is this was somebody who was deserving of the justice that he received. And I think Americans and people around the world are glad that he's gone. But we don't need to spike the football.”

To explain the political process. Consider how both Bill Clinton and Barack Obama used sports analogies to describe the state of their respective health care bills.

Clinton on Hillarycare: “I want to say one thing: As an ardent basketball fan, Lou made one minor error when he compared the victory of Schumer with the assault weapons with the victory of the Knicks over the Bulls. And it's very important for health care, so I'm going to leave you with this: The Knicks overcame a 15-point deficit and beat the Bulls with fabulous defense. Schumer passed the assault weapons ban by playing offense. We cannot pass health care unless we play offense, and that means people like you have to tell the Members of Congress it's okay for them to play offense and solve this problem.”

Obama on Obamacare: “Here's the problem, though, is when you've got all those things fitting together, it ends up being a big, complicated bill, and it's very easy to scare the daylights out of people. And that's basically what happened during the course of this year's debate. You--but here's the good news: We're essentially on the 5-yard line, for those who like football analogies. We've had to go into overtime, but we are now in the red zone. That's exactly right. We're in the red zone. We've got to punch it through.”

To talk about their record.

Eisenhower: “But all in all, there were 64, as I say, of these legislative projects submitted to the Congress. Now, 54 of them were enacted into law. We did not always make home runs. But we did have 54 hits. Some of them aren't quite what we wanted. But that, after all, is a batting average of .830, and any baseball fan will tell you that is pretty good going in any league.”

FDR: “A baseball park is a good place to talk about box scores. Tonight I am going to talk to you about the box score of the Government of the United States. I am going to tell you the story of our fight to beat down the depression and win recovery. From where I stand it looks as though the game is pretty well "in the bag."

To criticize the opposition.

FDR (1936): “When the present management of your team took charge in 1933, the national scoreboard looked pretty bad. In fact, it looked so much like a shut-out for the team that you voted a change of management in order to give the country a chance to win the game. And today we are winning it.”

And as a unit of measure.

George H.W. Bush (1992): “Last year, Americans expended 5.3 billion hours just to keep up with Federal regulations. That's like watching every pro-football game on television back-to-back for the next 12,268,000 years. [Laughter] That's not including playoffs.”

3. How presidents talk about sports

I have described four types of presidential sports rhetoric: 1. instrumental, 2. constitutive, 3. ingratiation, and 4. analogies/metaphors. The figure below shows how presidential sports talk falls into those categories. Ingratiation is the most common feature of presidential sports talk (5,917 references), followed by sports analogies and metaphors (2,247), constitutive rhetoric (2,185), and instrumental rhetoric (941).

Presidential Sports Talk by Category.

It is comparatively rare for presidents to spend time on instrumental rhetoric because there is usually not much profit in doing so. Bill Clinton, for instance, was widely criticized for his involvement in the 1994-95 MLB strike, an issue that even 72 percent of baseball fans felt was undeserving of the president’s attention. Rather than spending political capital on divisive topics in the sports world, most presidents opt for the rhetorical safe ground of recognizing athletic accomplishments, telling mildly amusing sports jokes, or using sports to constitute a national identity.

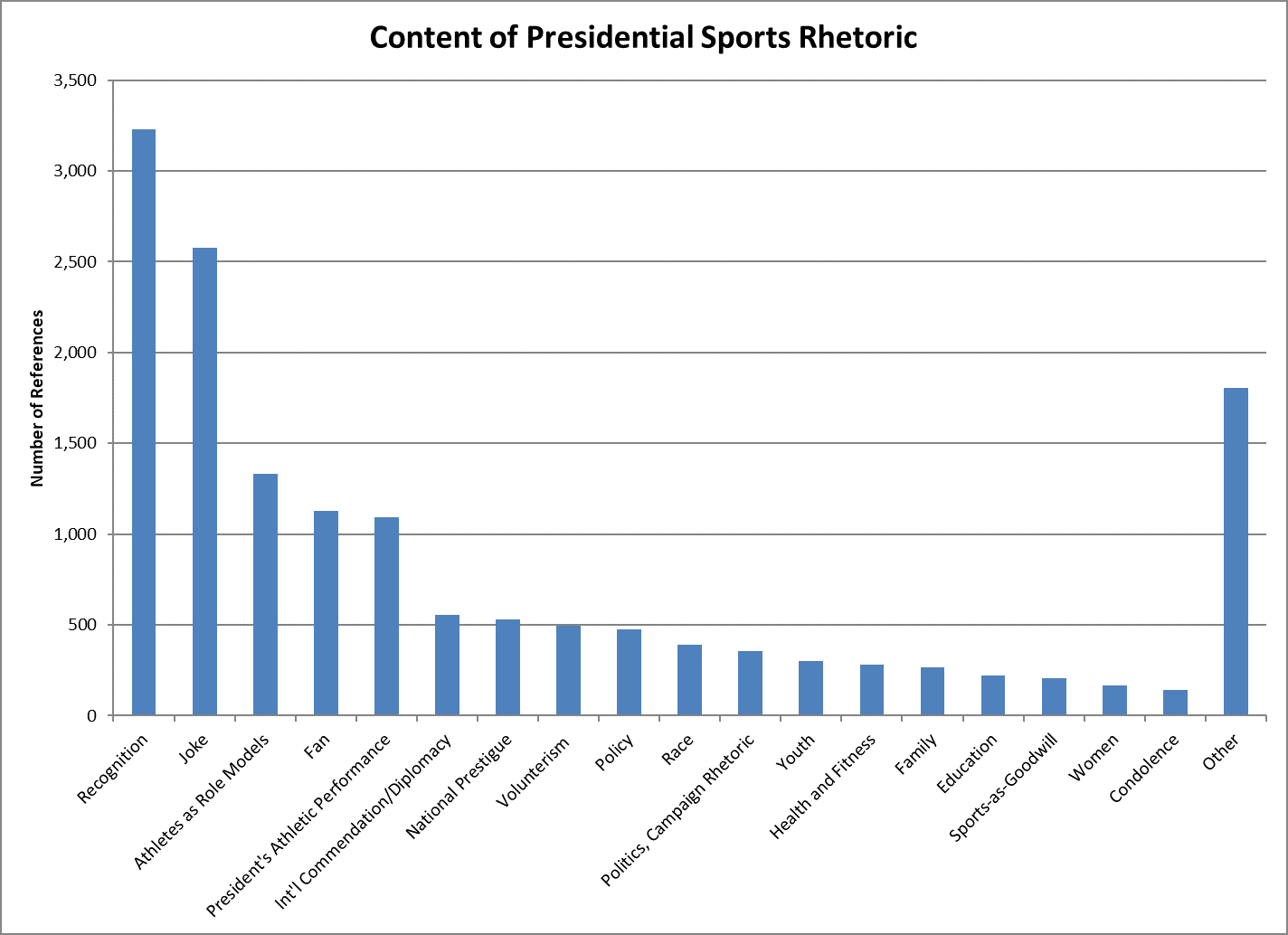

The next figure offers a disaggregated look at some of the more common features of presidential sports rhetoric. When discussing sports, presidents are most likely to recognize an athletic accomplishment (3,231 references) or tell a joke (2,576). Presidents are also quick to point out athletes as inspirations or role models (1,330), engage in fan talk (1,127), or discuss their athletic endeavors (1,094).

Content of Presidential Sports Talk

Table 1 examines the distribution of sports talk by presidents among our four categories. Most presidents devote similar attention to similar themes, with Carter and Trump being the notable outliers. Carter spent an abnormal amount of time talking about policy (49%), which is not much of a surprise given the salience of the 1980 Moscow Boycott and the fact that Carter was, comparatively, not much of a sports fan. Likewise, Trump spent an unusual amount of time on instrumental rhetoric (24%), most of which was his “position-taking” on the NFL national anthem protests.

Content of presidential sports rhetoric by president.

Table 2 looks at the top eight categories of sports rhetoric and examines that distribution by president. Again, Trump is the notable outlier. Besides being more likely to talk about policy-related issues, Trump also spent far more time talking about race (12%) than any other president (on average, other presidents devoted about 2% of their sports rhetoric to the subject of race). Trump was also more likely to use sports in campaign-style attacks on political opponents (10%) than were other presidents (an average of 2% across all other presidents). Finally, it is notable that Trump rarely points to athletes as role models for Americans.

Content of presidential sports rhetoric by president.

Presidents are usually upbeat when talking about sports. Table 3 shows that while most presidents adopt a positive tone when talking about sports (94% overall), Trump was only positive in 58% of his comments. Trump’s sports rhetoric is also extremely polarizing (76%) compared with other presidents (an average of 5% across all other presidents). And when most presidents did say something polarizing, they usually tried to soften the blow by couching it in positive terms. As we will see in “Get That SOB Off the Field,” Trump rarely pulls punches or bothers with niceties.

Tone of presidential sports talk.

Unifying or Polarizing Sports Rhetoric by President.

In short, all presidential sports rhetoric sounds pretty much the same… except when it comes from Donald Trump.