Curt Flood, the Supreme Court, and Baseball’s Antitrust Exemption.

THE BOX SCORE

Baseball’s reserve clause allowed team owners to pay their players far below market value.

A pair of questionable Supreme Court decisions—Federal Baseball (1922) and Toolson (1953)—provided Major League Baseball with an exemption from antitrust laws. That meant MLB could, and still can, do things that would be illegal in most other industries.

The Courts and the U.S. Congress blamed each other for not doing something about baseball’s “illogical” exemption from antitrust law.

Outfielder Curt Flood challenged MLB’s antitrust exemption, and in 1972, the Supreme Court again sided with MLB.

Free agency was ushered in three years later by arbitration.

In 1998, Congress passed the Curt Flood Act, which was symbolic but not terribly effective.

THE Complete game

If I had one case to teach about the American government, it would be centerfielder Curt Flood. The Flood story tells us most of what we need to know about U.S. politics; it is a lesson in the separation of powers, checks and balances, race, economics, and power. It also features three of the stupidest decisions ever handed down by the Supreme Court, decisions that shaped baseball throughout the 20th Century and still reverberate today.

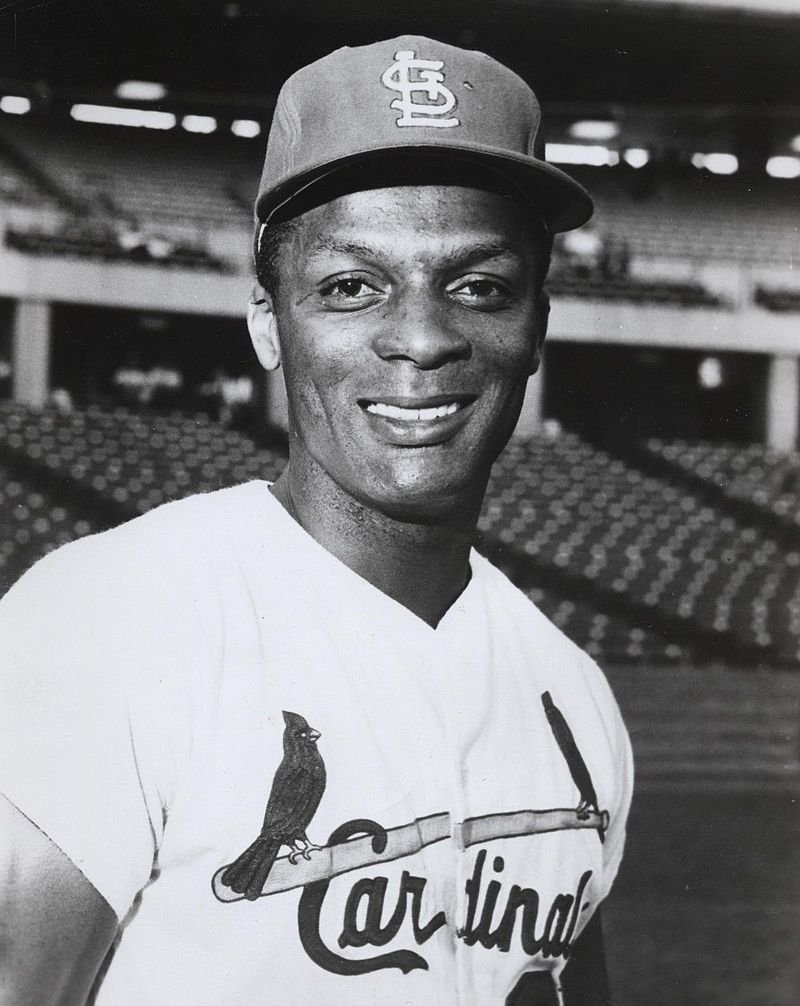

St. Louis Cardinals Outfielder Curt Flood. Source: St. Louis Cardinals/MLB https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=32369399

Curt Flood was one the best centerfielders of his generation: a lifetime .293 hitter, two-time World Series champion, three-time All-Star, and a seven-time Gold Glover for the Reds (1956-57), Cardinals (1958-69), and Senators (1971). But before we get to Curt Flood, we must travel back in time.

Baseball’s Reserve Clause and Antitrust Law.

In 1887, professional baseball formalized the longstanding practice of adding a “reserve clause” to players’ contracts. Once a ballplayer signed with a team, the reserve clause bound him to that team for the rest of his career. The team could cut or trade the player at will, but the player had no say in the matter.

There were many consequences of the reserve clause, one of which is that it severely depressed players’ salaries. Players could not sell their talents to the highest bidder, so they had to accept whatever paltry salary the owners offered, which was far under market value. In the reserve clause era, owners truly owned their players.

Just as baseball owners were tightening their grip over their players, the U.S. government was growing increasingly concerned with anticompetitive economic practices. In the Gilded Age of the late 19th Century, several businessmen had cornered the market in their respective industries: JP Morgan (banking and finance), John D. Rockefeller (oil), Cornelius Vanderbilt (railroads and shipping), and Andrew Carnegie (steel). The American public soon learned that a market economy does not work when monopolies or trusts exist.

Air Jordan 15s. Source: https://www.kickscrew.com/collections/air-jordan-15

Monopolies occur when one company controls an entire industry. A “trust” has several economic meanings, but here, it describes the practice of several businesses or individuals conspiring to control an industry. There is no competition if a monopoly or a trust dominates an industry. And if there is no competition, there is no incentive for a company to give consumers a good product at a reasonable price or pay their workers what they are worth. Imagine if Nike were the only shoe company; we’d all be wearing those ugly Air Jordan 15s.

At the turn of the 20th Century, Congress passed several laws introducing competition into the American economy. The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 prohibits activities restricting marketplace competition, including monopolies and trusts. The Clayton Antitrust of 1914 strengthened antitrust law by, among other things, outlawing anti-competitive mergers and predatory pricing. In 1911, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Standard Oil violated the Sherman Antitrust Act and broke it into several companies. Would the Court soon do the same with professional baseball?

The Federal Baseball Decision

In January 1915, the upstart Federal League filed suit alleging the National and American Leagues constituted a monopoly of professional baseball. The case was brought before federal judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who would eventually become baseball’s first commissioner. Privately, Landis sided with the Federal League but worried ruling so would destroy professional baseball. So, Landis delayed his decision until after the 1915 season. By then, the Federal League had dissolved, and most of their teams were absorbed into the National and American Leagues. One team that was not bought out, the Baltimore Terrapins, continued with the suit, alleging that the American and National Leagues violated the Sherman Antitrust Act.

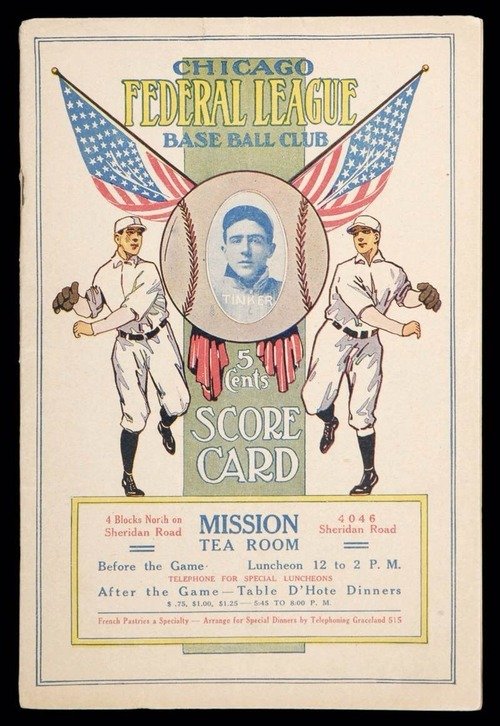

Program from the Chicago Whales of the Federal League. Source: https://fedball.com/history

In Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore, Inc. v. National League of Professional Baseball Clubs et al. (1922), the Supreme Court ruled that baseball was not interstate commerce and, therefore, not subject to the terms of the Sherman Antitrust Act. At that time, the Courts held a very narrow interpretation of the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution, which gives Congress the right to regulate interstate commerce. At first blush, baseball seems to fit the definition of interstate commerce: professional baseball teams travel across state lines to play games. But what mattered to the Court was that ballgames were played within a state; it didn’t matter how teams got there. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote in the Opinion of the Court, “Transport is a mere incident, not the essential thing.” As a result, professional baseball was allowed to act as a legal monopoly.

The Mexican League Controversy and the U.S. Congress.

After World War II, the Mexican League began siphoning players from the American and National Leagues by ignoring the reserve clause and offering higher salaries. Most players who jumped to the Mexican League soon found the extra money wasn’t worth it and tried to return to the States. In a move somewhat reminiscent of the recent PGA and LIV flap, baseball commissioner Happy Chandler banned the contract jumpers for five years. Outfielder Danny Gardella sued, claiming Major League Baseball acted as a monopoly. In 1948, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals agreed, ruling baseball was interstate commerce and subject to the terms of the Sherman Antitrust Act. Major League Baseball appealed, but Gardella and MLB settled before the Supreme Court heard the case.

Many observers thought the Gardella decision was the beginning of the end of MLB’s monopoly. The Court had adopted a modern vision of interstate commerce in the years since the Federal Baseball decision, and baseball seemed to fit the bill. Sensing a change in the judicial wind, several ballplayers followed Gardella by suing Major League Baseball for illegally restraining trade.

It was around this time that Congress got into the game. In the summer of 1951, the House Subcommittee on the Study of Monopoly Power considered whether baseball should be subject to antitrust law. After three months of hearings and hundreds of hours of testimony, the Subcommittee produced a 200-page report with one key recommendation: do nothing.

The Subcommittee found that “Congress has jurisdiction to investigate and legislate on the subject of professional baseball.” Nevertheless, testimony from Ty Cobb and others may have convinced some members of Congress that baseball’s immunity from antitrust law, particularly the reserve clause, preserved the competitive balance in the league. As economist Andrew Zimbalist and others have shown, the “competitive balance” argument for the reserve clause was a bunch of crap. But whether members of Congress recognized the argument as such is immaterial; the real reason for congressional inaction ran much deeper.

Simply put, members of Congress did not want to bring baseball under the terms of antitrust law because they did not want to be seen messing around with America’s pastime. Most of the American public, the sports media, and even baseball’s biggest stars felt that Congress should stay out of the ballgame. Representative Kenneth Keating (R-NY) echoed the prevailing sentiment when he said, “Congress better be darned careful before it starts tampering with baseball… At a time when the world is on fire, it seems to me that we have better things to do.” As Stephen Lowe writes in The Kid on the Sandlot: Congress and Professional Sports, 1910-1992, “[baseball’s] success in projecting an image of a game played by kids on sandlots across the country has continued to protect organized baseball’s privileged position under the antitrust laws” (p. 2).

The Toolson Decision

As Congress was holding its hearings, the question of whether Major League Baseball constituted an illegal monopoly was again weaving its way through the courts. George Earl Toolson was a minor league pitcher who filed suit against the Yankees in 1950 after they demoted him from AAA to A-ball. Toolson felt he was good enough to pitch for another big-league club, yet the Yankees denied him that opportunity because of the reserve clause, which, he claimed, constituted an illegal restraint on trade.

In Toolson v. New York Yankees, Inc. (1953), the Supreme Court again sided with Major League Baseball, citing the earlier Federal decision and the principle of stare decisis (“let the decision stand.”). As discussed in Five Lessons on the Federal Judiciary, Courts generally uphold past rulings (i.e., stare decisis) unless there is a good reason to overturn precedent. And it seemed like the Court now had a good reason. Unlike the earlier Federal Baseball decision, the Court recognized that baseball was interstate commerce. However, the Court noted that it was Congress’s job to bring professional baseball under the terms of existing antitrust law, not theirs. Therefore, the Court ruled that baseball was exempt from all antitrust laws until Congress said otherwise. (It is important to note that the Toolson case gave baseball an antitrust exemption; the Federal decision said baseball wasn’t interstate commerce, so no exemption was necessary.)

The Toolson ruling was strange for several reasons. First, the Court abdicated its role as the final arbiter of the law by kicking the can back to Congress. Second, the Court implied without evidence that Congress intended to exempt baseball when they passed the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890. Finally, shortly after the Toolson decision, the same Court ruled that professional boxing (IBC v. U.S., 1955) and the NFL (Radovich v. the National Football League, 1957) were subject to antitrust laws. So, for decades, baseball was the only major American professional sport allowed to act entirely as a legal monopoly.

With the Toolson decision, it was now up to Congress to act. And the legislative branch did what it does best: talk a lot and do nothing. Despite numerous hearings, hundreds of hours of testimony, and dozens of bills, Congress failed to pass a single bill concerning baseball’s antitrust exemption until the Curt Flood Act of 1998 (see A Useful Threat: Congress and Sports Antitrust Exemptions).

Curt Flood

In 1956, Curt Flood, a promising young outfielder from California, signed a contract with the Cincinnati Reds and attended their training camp in Tampa, Florida. Flood and his Black teammates were not allowed at the whites-only team hotel but had to stay at Ma Felder’s boarding house across town. Flood recalled his experience as a Black player during the Jim Crow era:

“Most of the players on my team were offended by my presence and would not even talk to me when we were off the field. The few who were more enlightened were afraid to antagonize the others. The manager, whose name mercifully escapes me, made clear his life was already sufficiently difficult without contributions from me. I was completely on my own.” https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/curt-flood/

Flood was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals in 1958 and became one of the best centerfielders of his generation. His experience with racism also fueled a passionate and principled social activism. Flood spoke at an NAACP civil rights conference in 1962, marched at rallies with Jackie Robinson, and sued to integrate his Alamo (CA) neighborhood despite repeated death threats.

In 1968, Flood hit .301 and took the Cardinals to the World Series. Unfortunately, Flood misjudged a liner in Game Seven against the Detroit Tigers, which helped cost the Cardinals the Series.

The 1969 season did not go well for Flood and the Cardinals. Flood asked for $90,000 in the off-season, but the Cardinals only gave him a $5,000 raise for a total salary of $77,500. To make matters worse, Cardinal owner August “Gussie” Busch gave a pre-season speech in which he berated his players for being greedy and attempting to unionize, a speech that seemed aimed at Flood and pitcher Bob Gibson.:

“Too many fans are saying our players are getting fat, that they only think of money, and less of the game itself.” Busch said. “The fans will be looking at you this year more critically than ever before to watch how you perform and see whether you really are giving everything you have.”

Gussie Busch was something of an enigma. He did more than any other owner of his generation to bring Black players to the majors and create an integrated squad, even buying a hotel in St. Petersburg, Florida to avoid the city’s “whites only” lodging policy during Spring Training. The 1969 Cardinals payroll was also the highest in the MLB. However, it seems ironic that one of the ten wealthiest men in America—a man worth an estimated $250 million—couldn’t find an extra $12,500 to pay what his Gold Glove centerfielder was asking. But such has long been the story of professional sports: players are branded as “greedy” in a way millionaire/billionaire owners are not.

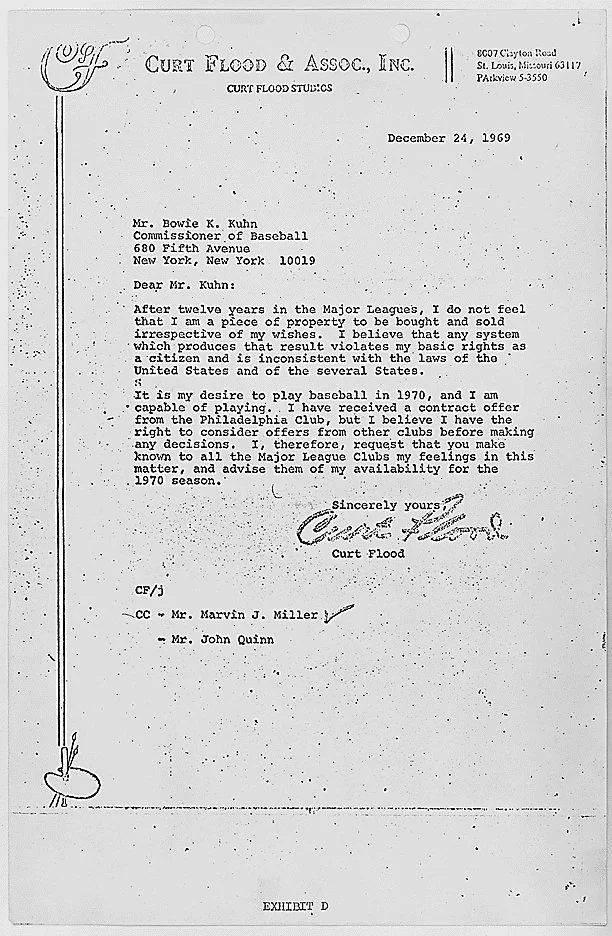

The irony was not lost on Curt Flood. On October 8, 1969, the Cardinals traded Flood to the Phillies. Flood did not want to go to Philadelphia and wrote MLB Commissioner Bowie Kuhn asking to become a free agent:

“After twelve years in the Major Leagues, I do not feel that I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes. … I believe I have the right to consider offers from other clubs before making any decisions. I, therefore, request that you make known to all Major League clubs my feelings in this matter, and advise them of my availability for the 1970 season.”

Curt Flood’s letter to MLB Commissioner Bowie Kuhn asking to become a free agent. Source: Curt Flood. (2024, February 14). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Curt_Flood

Kuhn rejected the request, leaving Flood with four options: (1) retire, (2) sit out a year, (3) play for the Phillies, or (4) sue in federal court.

Flood knew winning in court was a long shot. Marvin Miller, the MLB Players Association’s executive director, told Flood that even if he did win, he was unlikely to see any fruits of the victory since he would be effectively banned from MLB. However, Flood’s experience with racism led him to take a principled stance. Flood said,

“In the history of man, there’s no other profession except slavery where one man is tied to one owner for the rest of his life. Me as a Black man, I’m probably a lot more sensitive to the rights of other people because I have been denied these rights.”

Flood sued in federal court, arguing baseball’s reserve clause violated the Sherman Antitrust Act and the 13th Amendment of the Constitution, which forbids involuntary servitude. After losing in federal district and appellate courts, the Supreme Court agreed to hear Flood’s case in 1972.

In Flood v. Kuhn (1972), the Supreme Court issued a 5-3 ruling against Flood. The Court justified its ruling on the principle of stare decisis set by the Federal Baseball and Toolson decisions. And, again, the Court blamed Congress for failing to place baseball under existing antitrust law. In a rather unusual summary that reads almost like a mea culpa, Justice Harry Blackmun wrote:

1. Professional baseball is a business, and it is engaged in interstate commerce.

2. With its reserve system enjoying exemption from the federal antitrust laws, baseball is, in a very distinct sense, an exception and an anomaly. Federal Baseball and Toolson have become an aberration confined to baseball.

3. Even though others might regard this as “unrealistic, inconsistent, or illogical,” see Radovich, 352 U.S. at 352 U. S. 452, the aberration is an established one, and one that has been recognized not only in Federal Baseball and Toolson, but in Shubert, International Boxing, and Radovich, as well, a total of five consecutive cases in this Court. It is an aberration that has been with us now for half a century, one heretofore deemed fully entitled to the benefit of stare decisis, and one that has survived the Court’s expanding concept of interstate commerce. It rests on a recognition and an acceptance of baseball’s unique characteristics and needs.

4. Other professional sports operating interstate -- football, boxing, basketball, and, presumably, hockey and golf -- are not so exempt.

5. The advent of radio and television, with their consequent increased coverage and additional revenues, has not occasioned an overruling of Federal Baseball and Toolson.

6. The Court has emphasized that, since 1922, baseball, with full and continuing congressional awareness, has been allowed to develop and to expand unhindered by federal legislative action. Remedial legislation has been introduced repeatedly in Congress, but none has ever been enacted. The Court, accordingly, has concluded that Congress as yet has had no intention to subject baseball’s reserve system to the reach of the antitrust statutes. This, obviously, has been deemed to be something other than mere congressional silence and passivity. Cf. Boys Markets, Inc. v. Retail Clerks Union, 398 U. S. 235, 398 U. S. 241-242 (1970).

7. The Court has expressed concern about the confusion and the retroactivity problems that inevitably would result with a judicial overturning of Federal Baseball. It has voiced a preference that, if any change is to be made, it come by legislative action that, by its nature, is only prospective in operation.

8. The Court noted in Radovich, 352 U.S. at 352 U. S. 452, that the slate with respect to baseball is not clean. Indeed, it has not been clean for half a century.

This emphasis and this concern are still with us. We continue to be loath, 50 years after Federal Baseball and almost two decades after Toolson, to overturn those cases judicially when Congress, by its positive inaction, has allowed those decisions to stand for so long and, far beyond mere inference and implication, has clearly evinced a desire not to disapprove them legislatively.

In sum, the triumvirate of decisions by the Supreme Court established and maintained baseball’s right to act as a legal monopoly. The Federal Baseball case said baseball wasn’t interstate commerce. The Toolson case noted that baseball was interstate commerce but not covered by the Sherman Antitrust Act. The Flood case then relied on those two dubious precedents to maintain baseball’s antitrust exemption. Along with justifying its decisions via stare decisis, the Court consistently said Congress was the branch responsible for doing something about baseball and antitrust. In essence, the Court relied on two time-honored justifications for stupid decisions: (1) “We’ve always done it like this,” and (2) “It’s someone else’s fault.”

Arbitration and Baseball Free Agency

Although Flood lost in federal court, his activism awakened MLB players and fans to inequities in player contracts. Under pressure from its players, the MLB accepted binding arbitration as part of the Basic Agreement of 1970. That agreement meant that players could now take their labor disputes to an independent arbitrator, who would rule in favor of the player, the owner, or split the difference.

In 1975, three years after the Supreme Court’s Flood decision, an independent arbitrator ruled in favor of players Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally, effectively ushering in a system of free agency after the player’s sixth year with a team.

The fact that the Messersmith-McNally decision, not the Flood case, brought about free agency is notable for a couple of reasons. The first is the obvious racial component: Messersmith and McNally are White; Flood is Black. It is debatable how much race influenced the outcome of either case, but the perception is that it mattered. Second, it is unsatisfying that baseball’s free agency came through arbitration and not through the Courts or Congress. To my way of thinking, Flood had a home run of a case against MLB and did what Americans should do when wrongdoing occurs: petition the government for a redress of grievance. I find it unconscionable that the Courts admitted a problem existed but failed to do anything about it.

The Curt Flood Act of 1998

While Flood didn’t win in Court, he had a posthumous victory in Congress with the passage of the Curt Flood Act of 1998. The Act amended the Clayton Antitrust Act to cover baseball’s labor relations, giving baseball players the right to sue in federal court antitrust labor claims.

However, the Act is limited in several ways. First, it applies only to labor and does not touch other aspects of baseball’s antitrust immunity, including franchise relocation, broadcasts, or merchandising. Second, the Act excludes minor leaguers, which we will take up in MLB’s Antitrust Exemption. Finally, Zimbalist points out that the Act has little practical value because of yet another Supreme Court ruling. In Brown v. Pro Football, Inc. (1996), the Court ruled that players could either have a union (which is, by nature, anti-competitive and so covered under the National Labor Relations Act) or the protection of antitrust laws, but not both. Zimbalist writes, “The Brown decision thereby makes it more difficult for the MLBPA to take advantage of the antitrust tool it is granted in the Curt Flood Act” p. 23.

While Congress had finally passed a law revoking part of baseball’s antitrust exemption, it was, in the words of law professor Edmund Edmonds, “a hollow gesture.”

The Utility of Baseball’s Antitrust Exemption

Although I’ve been critical of baseball’s antitrust exemption regarding the reserve clause, I think some anti-competitive economic practices are needed to produce better on-field competition (see MLB’s Antitrust Exemption). To preserve a competitive balance, leagues must do things that would be illegal in most other industries, like holding a reverse-order snake draft, setting a salary cap or luxury tax, and engaging in revenue sharing. And it is good for fans that leagues restrict the movement of their teams.

I’ve also been critical of the Courts and Congress for not striking down, or at least modifying, baseball’s antitrust exemption. But, ironically, the continued antitrust exemption gives the government more leverage over baseball. Whenever baseball does something shady, Congress holds hearings and writes bills that threaten to remove its antitrust exemption. That threat is often enough to get MLB to resolve strikes or lockouts, test players for steroids, expand the number of teams, or pay minor leaguers a living wage. We will explore this further in A Useful Threat: Congress and Sports Antitrust Exemptions.